In 2003 my wife and I visited Australia for three weeks, spending part of that time in the harsh desert at the center of the continent, one of the hotbeds of thorny devil activity. We saw many wonderful wild creatures, but no thorny devils. (As a consolation prize, I did get to hold a captive thorny devil for a minute or two.)

In 2005 my wife and I, along with another couple, visited Australia again as part of a trip that also included New Zealand. Our time in Australia was spent in Western Australia, between Perth and Shark Bay. Thorny devils don't live as far south as Perth, but Shark Bay is solidly in their range. I did the things one is supposed to do when looking for thorny devils, but was rewarded only with not one but two expired devils. One had been flattened on the road, clearly earlier that same day. The other was a desiccated husk in the desert, which filled me with excitement for a moment, before shattering my dreams. (Who sees desiccated husks of reptiles? Especially the very reptile that they were most hoping to find alive? That is just weird.) As in 2003, the trip was great, because it is difficult to visit Australia and not see all sorts of amazing animals, but it was sadly lacking in live wild Moloch horridus.

My next attempt was in 2009, when my wife and my sister and I took the Perth to Shark Bay trip again, as well as visiting Kakadu and other northern destinations. Once again, did I see any thorny devils? No I did not. I didn't even see any ex-thorny devils this time. This was getting ridiculous. Thorny devils are quite common within their range, say all the books. (Though the books do admit that with their amazing camouflage and slow movements they are not actually easy to find.)

In late 2014 I started planning another trip to Australia. This time I would be going by myself, so I could spend essentially all of my time herping. (My wife, sensible person that she is, prefers to mix in other activities on her travels.) This time I did more research to determine the best time of year to find thorny devils, and the best places to look for them. I wanted to see a wide variety of herps in addition to Moloch, so I studied maps showing which species had been seen where and at what time of year. I got excellent advice from various helpful people, including Andrew Hodgson, Aaron Fenner, and David Fischer. My plans converged to the month of October, 2015. I would spend that entire month in Australia, seeking thorny devils and whatever other critters I could discover.

Here's my write-up of that month, split across eight pages to prevent your web browser from exploding. (I worked on Apple's Safari web browser for eleven years, so I know about these things.)

I flew across the world for about a thousand hours and finally touched down in Sydney. If you know your Thorny Devil range (which you do, right?), you will realize that I was not going to find any thorny devils near Sydney. I spent a few days near Sydney anyway, partly to get used to the 18-hour time zone difference from my California home, but more importantly to get a chance to spend time with David Fischer, who lives in that area. David is an extraordinary naturalist, and he and his wife Angie are the nicest couple you could ever hope to meet. David and I had "met" each other on fieldherpforum.com and FaceBook and through email, but never in person until now. He devoted a few days of his very busy schedule to hosting me at his home and taking me out herping.

After arriving in Sydney early in the morning and renting a car, I drove to David's home. One quick shower later, and Australian Herping Time officially began. (AHT is like Daylight Savings Time, but better in every way, including being nothing like Daylight Savings Time.) David took me first to a beautiful spot called Carrington Falls.

We quickly came across some Eastern Water Skinks, shiny, medium-sized skinks that as you might expect are often found near water, into which they will not hesitate to flee if disturbed. (I should point out now that Australian lizard sizes are on a different scale than U.S. lizard sizes. For example, a "medium-sized" Australian skink is the size of a "very large" American skink. But also, a "tiny" Australian skink is the size of an "extremely tiny" American skink.)

We waded through some shallow water to a spot where David had seen Cunningham's Skinks before. Cunningham's Skinks are large ("huge" in American), attractive, communal, rock-dwelling skinks that every sensible visitor would love to find. They are also quite shy, and we attributed our failure to find any of them to the number of people frolicking about in the general area.

Our consolation prize was a glimpse of a Grass Skink as it scurried away. This wasn't a particularly valuable consolation prize, because these small skinks are very common and not particularly interesting. And I didn't even get a decent picture. Nonetheless, here it is:

David took me to a spot on Mt. Keira where we had a high probability of finding a couple of skinks more interesting than the poor maligned Lampropholis guichenoti. We looked under some rocks and logs and pieces of tin and quickly uncovered the two we were looking for. First we found the Three-toed Skink, which is the sole member of its genus (See? I told you it was more interesting than L. guichenoti!). Skinks in Australia come with all sorts of finger/toe quantities. Never more than five per limb, to my knowledge, but beyond that almost anything goes. These ones have three digits on each of their four limbs. (Skinks in Australia also vary in their limb count, with four, two, and zero all being popular values.)

Under the same collection of movable objects we also found McCoy's Skink, which is also the sole member of its genus (See? See?). They come complete with the maximum complement of skinkian limbs (four) and digits (five per limb).

Under a piece of tin that also covered some of the aforementioned skinks lurked my first frog of the trip. This is a Striped Marsh Frog, a species I had seen before in Queensland but was happy to encounter again in New South Wales. They are common enough in their range that one of their common names is simply "Brown Frog". But that's a bit misleading, as they have a distinctive, attractive pattern.

Shortly after we left the skinks-and-frog spot we saw a medium-sized lizard (again, "very large" in American) in the middle of the road. We stopped the car so I could try to get a picture but it had been spooked and ran into the roadside vegetation. This was an Eastern Water Dragon, a common species on the east coast. I ended up seeing only this one individual in my whole month of October, but then I was only in their range for the first three days. I did get one photo of it in the roadside vegetation before it disappeared completely.

We then visited another spot where David had had success finding various creatures under pieces of tin that had been helpfully scattered about. Every herper starts salivating a little when they see this:

This particular piece of tin sheltered a large skink ("gigantic" in American). This was an Eastern Blue-tongued Skink, way bigger than any U.S. skink and approaching the size of the largest Gila Monster. We noticed that one of its legs (not visible in this photo) was seriously injured long ago, which caused David to realize that he had seen this particular skink several years earlier. An old friend, just trying to mind its own business.

David noticed that some no doubt well-meaning person or persons had cleaned up the vast majority of the pieces of tin that formerly festooned this area. This act of public service meant that we had far fewer opportunities to uncover interesting herps than we had hoped. We did manage to find one other, a common species but one that was new to me, the Eastern Small-eyed Snake. It was in no mood to pose for photos, wanting only to burrow into the leaf litter and sand.

Under the same piece of tin, I was surprised and somewhat horrified to find a large writhing mass of ants, which I have since been informed are Golden-tailed Sugar Ants. As a herper, I am used to finding unexpected large quantities of ants under things, but I am not used to them being arranged in thick piles of squirming horror. Also, I'm surprised that the snake wanted to hang out nearby. I have since tried to Google for info on associations between small-eyed snakes and ants, and also on the proclivity of this ant species to form huge oogly balls of skin-crawliness. But I had no luck on either front.

Later, after a delicious home-cooked dinner (did I mention that David is an excellent chef too?), we went out to a rocky outcrop where David has often found a particularly nice type of local gecko. The evening was cool-ish, possibly too cool for reptilian activity, so we tried to keep our expectations low. The first interesting critter in our path was this impressive spider, which I have not identified:

We had inspected a significant portion of the rocky outcrop in a depressingly gecko-free manner when a slight discoloration on the rock turned out to be our target, the Broad-tailed Gecko. We quickly found three others, and they were all cooperative about holding their positions while we doomed their souls to photography.

We spent most of the next day in different parts of the Blue Mountains, which aren't especially blue but are quite beautiful.

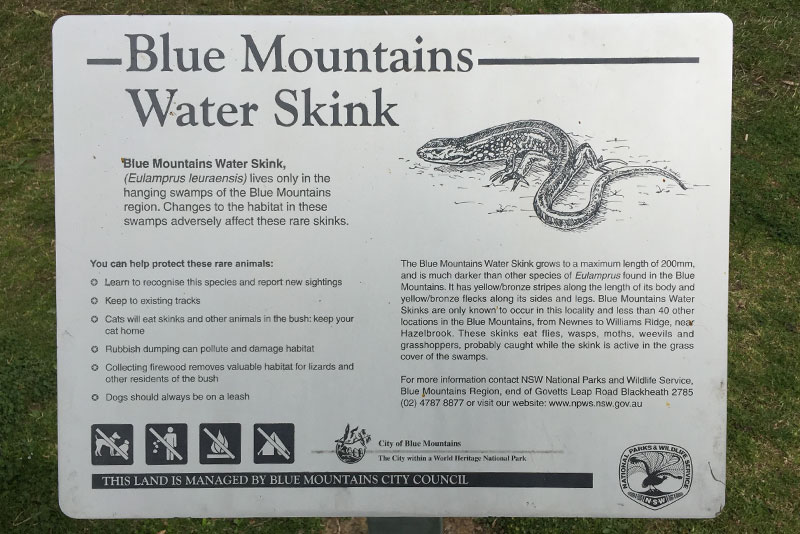

First we looked for the Blue Mountains Water Skink, which has a teeny-tiny range. We failed to find any in an area where David had seen them before, perhaps due to the cool, overcast weather. We did find a nice commemorative sign though:

At another Blue Mountains locale we looked for another population of Cunningham's Skinks that David had seen before. This time luck was with us and we spotted several shy little ones and one only-slightly-less-shy big one.

Near the Cunningham's Skink colony I spotted another type of skink that was new to me, the Copper-tailed Skink. Have I mentioned yet that Australia is home to more skink species than the human mind can comprehend?

We then hiked a trail at the poetically named Govetts Leap, where we saw (surprise!) more skinks. Most were tiny-to-small ones that vanished before we could photograph or identify them, but this Yellow-bellied Water Skink held its ground for a few moments.

The Blue Mountains were socked in by clouds all day, keeping the temperatures fairly low, and I was tiring out rapidly, so we didn't push it too much and headed back home for another delicious home-cooked meal. After dark we headed to Dharawal National Park to seek out some frogs. A decidedly non-froggy species that we quickly spotted was the Common Ring-tailed Possum.

The frogs we had hoped to find did not disappoint. We saw many Blue Mountains Tree Frogs, most of which were hunkered down on streamside rocks rather than honoring their common names.

Mixed in with the many Blue Mountains Tree Frogs were a handful of Stony Creek Frogs, which had the common decency to be hanging out alongside a stony creek.

The next day was very hot, record-breakingly so. We had originally intended to visit the popular Royal National Park, which is right along the coast, but decided that the combination of hot sunny weather and the day being an Australian holiday would mean so many visitors to Royal National Park that it would take us hours to park and then all of the reptiles would have been scared away by throngs of people anyway. So instead we visited nearby Heathcote National Park, where there were not throngs of people, but most of the reptiles had been scared away by the intense heat. I got no photos of herps at all, and only brief glances of several skinks. But to my delight I did see my first ever wild monotreme, a Short-beaked Echidna.

By early afternoon I was completely exhausted by what I assumed was the combination of the heat and late-onset jet lag, and we headed back to the Fischer's abode where I napped the rest of the afternoon away.

David's wide-ranging naturalist interests have lately been concentrated on moths, and his back porch includes a (semi-?)permanent "moth cloth", which is a hanging sheet onto which is shined ultraviolet light, irresistible to moths. At some point after I arose from my fitful slumber, David showed me a back porch visitor that was taking advantage of this situation by snacking on the tastier winged insects. As punishment, this little skink had to pose for some photos in the backyard.

The next morning I was sorry to say goodbye to the extremely hospitable David and Angie, and I drove north towards Sydney. Since it was no longer a weekend or a holiday, I stopped at Royal National Park and hiked the trail that we had originally planned to hike the previous day. I saw a Yellow-faced Whipsnake (Demansia psammophis) on the road into the park, but it skedaddled before I could get any photos. A little later in the morning I came across another snake crossing the trail, but it too escaped unphotographed and I couldn't match my memory of its appearance definitively to any of the local species. (It was the size and shape of an average U.S. gartersnake, dark in color, without any obvious patterning.)

I saw several more Eastern Water Skinks and Copper-tailed Skinks and various Small Nondescript Photography-evading Skinks, but nothing of special note on the rest of the hike. The hike quickly drained what little energy I had woken up with, but the beautiful scenery took my mind off of my exhaustion and my lack of new herps to photograph.

I then made it back to Sydney and rested for the remainder of the day, with the next leg of my trip scheduled to begin with the following morning's flight to Alice Springs. Would the rest of my entire trip be scuttled by my mysterious lack of stamina? Read on to find out!

Next: Alice Springs and Yulara