After my brief stay in Kimba, I had only three nights left in my month o' herping. The final night was to be near the airport in Adelaide, so the following morning I could begin the lengthy process of flying back to California. The two nights before that I would spend in Port Lincoln, on the southeast coast of the Eyre Peninsula.

On the way south, I took a minor detour to visit one of several parks in the center of the peninsula. The one I chose was Hincks Conservation Park, a large mallee ecosystem. Access involved a road that progressively degenerated in both width and quality as it approached the park, to the point where I was quite unsure that it would reach any destination before fizzling out entirely. But eventually I did come across a park sign and soon thereafter I found myself in habitat that looked like this:

The park is an undeveloped patch of wildness except for this one barely usable dirt road running through part of it. I just drove in until there was a reasonable-looking place to pull the car over, then got out and hiked around to see what I could find. It didn't take too long before I spotted a glimpse of a small lizard speedster disappearing into a bush. I poked around for awhile but failed to see that one again. Soon enough I saw a couple more and got a few photos.

It was now mid-morning and I wanted to check out Coffin Bay on the southwest side of the peninsula before heading east to Port Lincoln, so I left Hincks and continued south. An hour or two and several Shinglebacks later I pulled into a viewpoint overlooking the town of Coffin Bay and ate a quick lunch. I noticed a sign for Kellidie Bay Conservation Reserve on the far side of the parking area so I thought I'd have a quick look. Many hunks of concrete cried out to be looked under, and I heeded their cries. I soon uncovered the smallest skink of my trip. A few of these could curl up on a Shingleback's tongue.

Under another nearby hunk of concrete I found a smallish dragon, which took offense at my presence and ran around in crazy circles for a few seconds before dashing back under the nearest cover. We played this game together, the dragon and I, for a few minutes. Eventually the lizard must have figured out that I would go away if it would just let me take a few photos, so it settled down. It didn't look like any lizard I had yet seen on this trip, but I also couldn't find any other candidate lizard in my trusty Wilson and Swan field guide.

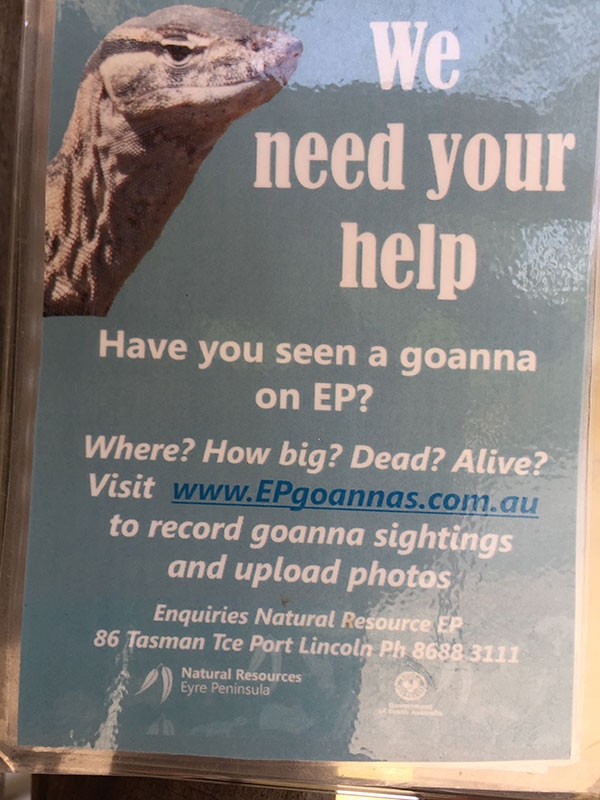

Soon I found myself entering Coffin Bay National Park. In addition to myself, I also found this sign. A whole website devoted to reporting monitor lizard sightings? Somebody's priorities are in the right place.

Soon enough, I saw a large report-worthy lizard strolling across the road. I followed it into the roadside vegetation for a couple more photos before it grew wary of me and raced off.

Half an hour later, I saw another. This one vanished into the bush and I couldn't spot it again on foot. Naturally I reported both sightings to the website on the sign. Later I got a "Happy Holidays" email from them, wishing for more goanna sightings in the new year. I too wish for that!

It would be wrong of me not to throw in another Shingleback here.

Coffin Bay didn't cough up any other new species for me that afternoon. It was too cold at night to bother looking for nocturnal herps. The next morning I headed over to Lincoln National Park, across the peninsula from Coffin Bay, and kept driving until I reached a beautiful ocean viewpoint.

But I wasn't hear to admire the scenic beauty! There were potential herps to be found! The habitat near the viewpoint looked promising, with large slabs of limestone exfoliating smaller boulders and rocks.

Indeed, some lizards started showing up after awhile. They were small dragons, which I assumed (correctly, it seems) were the same type I had failed to identify at Kellidie Bay the previous day. Occasionally I could sneak up on one for a few photos, but more often they would see me and dash into the nearest crevice or under the nearest loose rock. If they chose the latter path, I could turn the rock, and play that game again for a while.

After I got back home and studied my photos more carefully, I still couldn't figure out which species these were. I determined that they were Ctenophorus, but I needed to get help from knowledgeable folks to eventually decide that they were the local form of Peninsula Dragon, Ctenophorus fionni. This was a species I had seen in the Gawler Ranges in the northern Eyre Peninsula, but these new ones were much smaller and more drably colored than the Gawler Ranges animals. It seems that this species is distributed across a number of isolated populations, and there is considerable variation in size and coloration between populations.

As a reminder, here's what the Peninsula Dragons of the Gawler Ranges looked like:

I was lucky enough to see a couple more Heath Monitors in the early afternoon.

Near the trail monitor, I found one more new-to-me agamid. After I got this in situ photo, the lizard hopped off of its perch and tried to escape in the brush. It moved remarkably slowly, and I easily caught it to try to get it to pose for a less obstructed photo. But when I started fiddling with my camera, it ran toward me, then up my leg and my back until I felt it on my neck. And then I lost it. I was standing in the middle of the trail at this point and should have been able to see it try to escape on the ground, but I didn't. I assumed it must still be on my clothing and even took off my shirt to check the folds, but I never saw another sign of it.

Another one-off was this lone little basking Bright Snake-eyed Skink. I was surprised to only find one individual of this genus in this area, since in my experience they are typically among the most common herps in any given area of Australia.

Near the Cryptoblepharus I found a few super squiggly burrowing skinks under logs. This was, alas, the final species of lizard from my trip.

But that doesn't mean it was the final species of reptile! In mid/late afternoon, as the sun began to sink, another welcome sight appeared in the road in front of me.

A little ways further down the road I spotted in the distance the familiar shape of a Shingleback that had just begun trudging its way across the pavement. Another photo op for my collection. But then I realized that the plodding skink was not alone; a dozen feet from it lay another Heath Monitor basking in the late afternoon warmth.

I spent a good long while carefully stalking and photographing the monitor. At one point it was spooked just enough to clamber to the road's shoulder, but not so spooked as to race off, so I took more pictures there. When I was satisfied, I remembered the Shingleback and assumed that it had traversed the road long ago. But one should never overestimate the energy level of a Shingleback. It had reached the center of the road and decided that now was as good a time as any to take a nap.

In honor of the ubiquity, awesomeness, and ridiculousness of this species, I will conclude my account with a photo of a tribute to Tiliqua rugosa I had run across in Coffin Bay National Park.

John Sullivan

January 2016