Last year I joined MT Amazon Expeditions for a herping trip to Peruvian Amazonia. I had such a great time that I decided to take the same trip again this year. I didn't have any specific target species this year, because last year we saw the best snake (Bushmaster) and the best lizard (Caiman Lizard). I just wanted to see and photograph as many different animals as possible in the glorious Amazon rainforest.

This year there were many fewer travelers than last year: just eight of us, compared to 18 last year. Here is a carefully posed shot of all eight of us. Or at least one of us is carefully posed. From left to right, Lorrie (MT Amazon Expeditions co-owner), Matt (trip leader), Kevin, John (me), Will, Rebecca, Rick, Bob.

Like last year, the trip started in the city of Iquitos, from which we took a speedboat downriver to the two first of the two forest stations. I'll just skip through this part quickly to get to the part with all the pictures of forest creatures.

Here's Lorrie climbing into the boat we took downriver.

The river is wide.

The travelers are dreaming of a herp-filled future.

Home Away From Home 1: Madre Selva Biological Station

Like last year, the first half of the trip was spent at Madre Selva Biological Station, which is owned by Project Amazonas. Since there were fewer guests this year, everyone got a tambo (local name of mysterious origin for, basically, "hut") of their own, other than the father-son team of Bob and Kevin. This meant that the big tambo that was used in previous years as the "bachelor pad" was instead available to be used as the photo studio. And this meant that the big tambo that was used in previous years as the photo studio was instead available to be used as the kitchen + dining room. And this was fortunate, since the building that was used in previous years as the kitchen + dining room was no longer available, on account of it having been torn down. So it's good that there weren't so many guests this year.

The Madre Selva tambos at the top of the hill, where most of us stayed (there are a few more tambos down the hill a bit). I had the first one on the right to myself. So much room!

Here's a goofy picture of this same scene, taken from the other side up on the observation tower. I used the "miniaturization" effect (a.k.a. "tilt/shift", though it's not *really* tilt/shift) on my recently-acquired Canon SX50 on a lark. So far this is the only photo I have ever taken with this effect.

Some people hung their clothes out to "dry" on lines. This was an interesting way to collect local wildlife.

Other local wildlife could be found without leaving the Madre Selva camp area. Like last year, a large Southern Turnip-tailed Gecko (Thecadactylus solimoensis) patrolled the inside of the bathroom building.

Cane Toads (Rhinella (Bufo) marina) were common in the grassy cleared area around the camp buildings. I didn't see any really huge ones this year, but there were plenty of small to medium-sized ones.

The plants along the edges of the grassy areas contained colonies of little treefrogs. This one is a Short-nosed Treefrog, Dendropsophus (Hyla) brevifrons.

An adjacent plant housed this Many-lined Treefrog, Dendropsophus (Hyla) haraldschultzi, and his colorful grasshopper companion.

At Madre Selva, the local villagers knew of our presence and our herp-loving nature, so they would catch local critters and bring them to us in canoes and other small boats. We would reward them with T-shirts and baseball caps that we had brought for this purpose. A lot of interesting and otherwise-unseen species came to us this way. For instance, a villager brought us this Common Bird Snake (Pseustes poecilonotus). This is a bulky, fast-moving diurnal species that I had only gotten a quick glimpse of last year in the forest.

These captured animals would be photographed around the camp area, sometimes posed on tabletops decoratively strewn with leaves and logs, and sometimes posed outdoors. After a day or so, they would be released in appropriate habitat. Here, Matt, Will, and Rick photograph the Pseustes on the ground while Edvin (about whom more later) looks on.

Here, Rick, Kevin, and Bob photograph the Pseuestes in a small tree, while Matt wrangles it.

The most popular animal brought to us by a villager was a beautiful 7 1/2 foot long Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus). Here, Will tries to convince it to pose nicely near the water's edge.

And he was successful, at first. Here is the anaconda posing nicely near the water's edge.

Eventually the anaconda got tired of being told what to do, and expressed its displeasure by biting Will. I had wandered away when I heard this news, but quickly returned in the hope of getting a newsworthy picture of Will being swallowed or perhaps merely dismembered. But alas, when I returned the snake was no longer biting Will. Instead, it was biting Matt, as well as constricting him, while a village youngster puzzled over the ways of the strange pasty-skinned folk.

With some assistance from Kevin, the hapless anaconda was eventually dislodged from all of Matt's limbs, making him (Matt, that is) a happy camper.

Home Away From Home 2: Santa Cruz Forest Reserve

The second half of the trip was spent at Santa Cruz Forest Reserve, also owned by Project Amazonas. It is closer to Iquitos, upriver from Madre Selva, and a little smaller and more primitive than Madre Selva. The Santa Cruz camp contains a total of five tambos, plus a larger central building (in the center of this photo).

The central building is divided into two parts with a walkway between them. The back part has the kitchen (including the precious Cooler That Usually Contains Cold Soda And Beer) and a small living space used by the caretakers. The front part has a large open area with a couple of picnic benches, along with a few more mosquito-netted beds and some storage. We used one picnic bench as the dining table...

... and the other picnic bench as the photo studio for captured critters.

A few yards to one side of the central building sits a small shed that holds a generator, two bathrooms, and two showers. Water for the bathrooms and showers is pumped from a pond that was formed by damming a small creek. The Ritz it is not, but hey, there are flush toilets and showers, and you're in the Amazon rainforest, so what's not to like?

Plenty of herps lurk in the cleared area and pond, so you never know what you might find by just stepping outside and looking around a bit. Here's a pair of amplexing Marbled Treefrogs, Dendropsophus (Hyla) marmoratus. Edvin (not a typo, but pronounced "Edwin"), the crew member with the keenest eye for finding herps, spotted these frogs about ten feet off the ground on a branch leaning against the kitchen building.

Just after I took the above photo of the amplexing treefrogs, I turned around to head back to my tambo. Five feet away, a snake stretched across the grass. I tried to get a photo in place, but the snake had other ideas and turned to head back into the forest. I recognized it as a species we had already encountered, and grabbed it so I could get photos later on. This is Oxyrhopus vanidicus, a species recently split from the Black-headed Calico Snake, Oxyrhopus melanogenys.

One afternoon, a beautiful young Collared Tree Runner (Plica plica) posed nicely for me on the trunk of a tree right next to the generator.

Another afternoon, I spent nearly an hour trying to get a decent photo of one of the many Giant Ameivas (Ameiva ameiva) that patrolled the grassy slope behind the central building. I failed in that particular goal, but I did get a few crappy photos.

Here's the aforementioned pond behind and down a small grassy slope from the Santa Cruz buildings. If you're in need of a quick frog fix at night, you need go no further.

The most numerous frog species at the pond is the Variable Clown Treefrog, Dendropsophus (Hyla) triangulum. Frogs of this species range from solid yellow to brownish to reddish to elaborately patterned.

Mixed in with all the triangulum are a lesser number of Polkadot Treefrogs, Hypsiboas (Hyla) punctatus.

Last year we found three species of Monkey Frogs (Phyllomedusa) around the Santa Cruz pond, and quite a few of each species. This year we didn't find any White-lined Monkey Frogs (Phyllomedusa vaillanti), and only this single individual Barred Monkey Frog (Phyllomedusa tomopterna). Something about the conditions must have been subtly different, affecting the frogs' behavior.

Fortunately, everybody's favorite monkey frog, the Giant Monkey Frog (Phyllomedusa bicolor), was still plentiful.

It is hard to resist putting a Giant Monkey Frog on your head, and I failed to resist.

Where the Wild Things Are, part 1: Daytime

So lots of wonderful animals could be found by meandering about the grounds of the two camps, or even sitting and waiting for local villagers to bring creatures to us. But nothing compares to the thrill of hiking through the Amazonian rainforest and seeing the incredible diversity of life there, firsthand. Our days were divided by mealtimes into three: between breakfast and lunch, between lunch and dinner, and after dinner. We could go hiking in the forest any or all of these three times each day. Mostly I did all three, though I hung around camp on a few rainy days, and went kayaking one morning (more about that later). Of course, different animals would be active by night than by day. I'll start with the day shift.

The constantly warm and wet forest incubated fungus like nobody's business. I liked the look of this little mushroom colony on a small branch close to the ground.

Amazonia is stuffed full of interesting bugs. Most of my favorites were active at night, but some choice specimens could be found during the day too. This bug had some impressively meaty and armored back legs.

Dragonflies of various sizes and color schemes zipped about, occasionally alighting on twigs and leaves for a few moments.

The leaves were patrolled by innumerable invertebrates, such as this eye-catching Pleasing Fungus Beetle (family Erotylidae).

Apparently some insects never learned to come in out of the rain.

Perhaps the most noticeable group of invertebrates (not counting mosquitos and ants) was the grasshoppers. Especially along the edges of the more open trails, every step was likely to send a few of them jumping out of the way. Many of them were particularly colorful, such as these two species in the family Acrididae.

My favorite day-active grasshoppers are these guys in the family Eumastacidae, called Airplane Grasshoppers. They buzz around like little biplanes.

I tend to not take many photos of birds, because my interest level isn't sufficient to overcome their difficulty-to-photograph level. But I like a pretty bird with a funny name, so I was happy to take a few shots of this trogon. (I'm not sure which trogon it is though; there are several candidates. I know it's not the Violaceous Trogon, which is the one with the funniest name, so that makes me a little sad.)

Daytime Frogs

Most of the frogs in the forest are active at night, but one can usually scare up a few anurans on a daytime hike too. The most commonly seen are Crested Forest Toads, in the species complex Rhinella "margaritifera". Last year I saw dozens and dozens of these, but this year they were not so abundant, though still more easily seen than other daytime frogs. They vary quite a bit in shape and coloration, and it's difficult to tell some of them apart from other Rhinella species that have been extracted from this complex. But I think these guys all qualify as R. "margaritifera".

The most beautiful specimen I saw was an itty bitty metamorph, maybe 3/8 of an inch long. Youngsters often have some blue color, which generally fades as they age. This tiny one was the bluest I've encountered.

The Sharp-nosed Toad, Rhinella (Bufo) dapsilis, is distinguished from the R. "margaritifera" complex from whence it sprang by its pointy snout and smooth skin. Last year I saw only one of these; this year I saw four or five.

Everyone's favorite diurnal Amazonian frogs are the poison dart frogs. The most commonly-seen species in the area (at least by me) is the Pale-striped Poison Frog, Ameerega hahneli. Here, a young A. hahneli is targeting a small cricket that you can see on the left side of the photo.

Alas! The cricket survived to taunt small frogs another day.

This similar-looking species is the Spotted-thighed Poison Frog, Allobates femoralis.

One morning I saw a half-inch brightly colored frog hop from one place to another on a broad leaf of a low plant. I recognized it instantly as a dart frog, but couldn't quickly make out the color pattern well enough to guess at the ID. No matter, I needed to get photos! I have an irrational love for natural light in photographs, and in the dark rainforest this generally necessitates the use of a tripod, so I kept one eye on the frog while setting up my tripod. Unfortunately the uncooperative frog chose to hop from its completely exposed position to the half-obscured position seen here. I got a couple of photos before it hopped away again, this time off the plant and down into the leaf litter. It quickly disappeared and I regretted not having caught it to bring back for others to photograph. But when I looked at my photos later, I realized that the frog was carrying tadpoles on its back, and this realization made me glad that I hadn't captured it. With only a small portion of the frog showing clearly, it's impossible to be sure, but I think this is probably Ranitomeya uakarii, a species that I had also seen the previous year.

Cocha Chirping Frogs, Adenomera andreae, prefer relatively open areas. We saw a few of them on a wide trail.

Broad-headed Rain Frogs, Strabomantis sulcatus, are easy to identify due to their big fat heads.

Common Big-headed Rain Frogs, Oreobates quixensis, are active both day and night. This tiny metamorph chose the former. They might be big-headed, but their heads are still less fat than those of Strabomantis sulcatus.

Most Pristimantis frogs are seen at night, but occasionally I would see one perched on a leaf or hopping in the leaf litter during the day. I believe this one is a Carabaya Rain Frog, Pristimantis ockendeni.

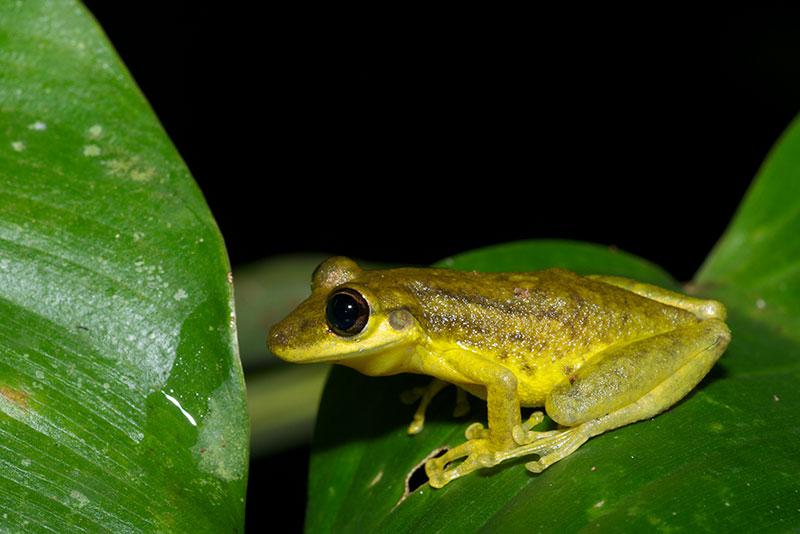

This bright yellow Rough-skinned Green Treefrog, Hypsiboas cinerascens, had chosen to sleep the daytime hours away in a fully exposed position on a leaf overhanging a small stream. I think it needs to do a little more reading on the concept of "camouflage".

Daytime Forest Lizards

Daytime lizard viewing was highly dependent on the amount of sunshine. When the sky was entirely overcast, it was rare to see a lizard. When the sun shone, lizards would often bask in open areas in the forest, and they would also be more easily encountered even in the darker areas.

The South American Spotted Skink, Copeoglossum nigropunctatum, is the only skink species in the area (this ain't Australia). They were easily observed at forest edges and in open areas, when the sun was out.

Forest Whiptails, Kentropyx pelviceps, would also scuttle around in sunny patches, rarely stopping long enough to be photographed.

A number of Anolis species inhabit the area, and all are active during the day. But they are generally easier to find at night, when they sleep on twigs and leaves. I only saw two species by daylight. The more plentiful, unsurprisingly, was the Common Forest Anole, Anolis trachyderma.

Edvin found this large adult Blue-lipped Forest Anole on a tree. It tried to frighten us away by holding its mouth open for a long time, but we were not frightened.

Two small diurnal gecko species inhabit the area, the Bridled Forest Gecko (Gonatodes humeralis) and the Collared Forest Gecko (Gonatodes concinnatus). Last year I saw plenty of both. This year I most likely did also, but when I went through my photos I couldn't find any that were definitively Gonatodes concinnatus. The first two here are certainly male Gonatodes humeralis, and I'm fairly certain that the third one is a female Gonatodes humeralis.

Some Amazonian lizards in the family Gymnophthalmidae, sometimes called Spectacled Lizards or Microteiids, can be found both day and night. The type I saw most often was the Black-striped Forest Lizard, Cercosaura ocellata bassleri. Mostly I saw very young ones with bright red tails, such as this one.

I didn't notice that this one was munching on a tiny cricket until I looked at my photos later.

After seeing a succession of youngsters both last year and this year, I finally saw an adult. This one is an adult female; the males are more distinctively patterned.

The other Gymnophthalmid that I saw during the day was the closely related Elegant Eyed Lizard, Cercosaura argulus. I saw a couple, but only got halfway decent photos of this one.

My favorite forest-floor lizard was the beautifully camouflaged Western Leaf Lizard, Stenocercus fimbriatus. Typically they would rely on their camouflage and hold their position unless you stepped within a few feet of them, whereupon they'd run five or ten feet away and then stop and hold their position again.

I was proud to notice this young Stenocercus fimbriatus without it moving. A first for me!

I saw a couple of diurnal lizard species by day for the first time this year. This Olive Tree Runner, Plica umbra ochrocollaris, clung to the side of a tree trunk that leaned over a forest stream.

And this Amazon Forest Dragon, Enyalioides laticeps, was basking in a small sunny patch when it was found by the eagle-eyed Edvin.

Daytime Forest Snake (note that I didn't say "Snakes")

I only saw one snake while hiking in the forest by day this year: this six-inch Short-nosed Leaf-litter Snake, Taeniophallus brevirostris. Daytime is not the best time to find snakes, though of course Edvin still managed to do so regularly.

Around and In the River

Three kayaks were available at Madre Selva, and one morning Lorrie, Matt, and I decided to take a paddle to see what could be found. Crew members took us and the kayaks upstream on a small speedboat and dropped us off so that we could avoid fighting the current. Ah, luxury. On the way out, we watched a troop of squirrel monkeys leap through the trees. This picture is here just in case you were hoping to see a picture of a monkey.

After being dropped off, we floated along happily, looking for critters in the riverside vegetation.

One of the interesting local species that is typically only seen right along the river is the Crocodile Tegu, Crocodilurus amazonicus. I had seen a couple of small ones last year, and even managed to grab one of them that had foolishly appeared in the water right next to my kayak. No tegu-touching occurred this time, but Matt and I did get a good view of an individual that was much larger than the two from last year. (Lorrie had grown weary of our leisurely pace by this point and paddled back towards camp, so she missed all the fun.)

Not too long after that, I was a little overzealous in my attempts to escape from an eddy without being grabbed by overhanging spiny vines, and I ended up taking an unplanned swim in the river. I couldn't decide whether I should worry more about the piranhas or the microbes, so I decided to just enjoy it instead. It didn't seem possible to right and drain the kayak while it was still in the river, so Matt and I had to come up with an alternate approach to avoid drifting with the current indefinitely. We tied the two kayaks together and Matt paddled toward the shore while I rode the toppled kayak and attempted to both prevent it from submerging and keep it away from the space in which Matt needed to paddle. This was slow going, but eventually we reached a swampy edge where I could stand and pull the kayak out of the water. Madre Selva's caretaker Julio had somehow (we never did figure out just how) discovered our predicament and come to help. He brought a half-coconut-sized scoop with which he bailed most of the river water from the kayak. No piranhas were encountered; I'm not so sure about the microbes. Fortunately, the camera I was carrying had been zipped into a bag at the time, and though the bag was submerged, the camera was undamaged (and my tegu pictures survived!).

Where the Wild Things Are, part 2: Nighttime

For the herpetologically inclined, the night shift in the rainforest is even better than the day shift. Most of the frogs and (I think) most of the snakes are active at night. Most of the lizards are not, but many of them are more easily found sleeping at night than active during the day. And the bugs are weirder, which is always nice.

First, some less-weird bugs. This is a Clearwing Butterfly, Mechanitis sp., sleeping at night.

Nighttime was filled with large moths, many of which unfortunately have similar orange eye-shine as some of the nocturnal snakes. This one wasn't particularly large or colorful, but I thought it had an attractive and subtle pattern. And it was posed nicely (if on the wrong side of the leaf).

We saw a lot of caterpillars, just a few of which I took photos of. Here's a particularly large and urticating-hair-covered one.

These were large and very bright, presumably warning predators away from toxins.

The very large Helicopter Damselflies fly slowly and apparently awkwardly, but are efficient predators of certain types of spiders, which the damselflies pluck from foliage and sometimes straight from webs.

Cockroaches look particularly creepy when they molt.

Cicadas, on the other hand, are particularly beautiful when they transform from nymph to adult.

I love phasmids, a.k.a. walking sticks, and the rainforest is packed with 'em. Unfortunately I don't know how to tell any phasmids from any other phasmids.

When I first encountered a jumping stick, I thought it was a walking stick. Then it jumped. Here's a mating pair of these wacky grasshoppers, Apioscelis sp.

Most of the short-horned (i.e., non-katydid) grasshoppers made themselves visible only by day. In addition to the jumping sticks, another exception was this leaf mimic Colpolopha species.

Katydids are very common and very diverse. I'll start with some miscellaneous (and all unidentified) species.

This one is a Conehead Katydid, Daedalellus sp. I would like to call it Beldar.

This unmistakeable beast is a Spiny Lobster, Panoploscelis specularis. I have never seen a larger katydid or grasshopper.

But my favorites are the amazingly cryptic leaf katydids in the tribe Pterochrozini (genera Pterochroza, Cycloptera, Roxelana, and Typophyllum). These insects look more like leaves than leaves do. This one is a Peacock Katydid, Pterochroza sp., which has an impressive spread-winged threat display. Unfortunately I know this only by reading about it later, rather than experiencing it firsthand.

These two might be Roxelana crassicornis.

And the rest of these are probably Typophyllum sp.

Incredible though the leaf katydids are, they were still only my second-favorite type of katydids in the rainforest. The winner was the aptly-named Spiny Devil Katydid, Panacanthus cuspidatus. Not only is this another type of Conehead Katydid, but its head-cone is a three-pointed red horn, and it has large green spines around its head and arms. And let us not forget the crazy eyes. Furthermore, when transforming from its nymph form, it hangs moistly and periodically wriggles, exactly like H.R. Giger's creature from the movie Alien.

At night the scorpions come out to dine. I think the (larger) black one is Tityus asthenes. I have no idea about the (smaller) brown one.

First in the category of Not Spiders (Really!) is this harmless but menacing-looking harvestman.

Next in the category of Not Spiders (Really!) is this harmless but menacing-looking mother tailless whip scorpion (amblypygid) and her writhing brood.

Of course there was no shortage of actual spiders either. Here are a few of the larger ones I saw. The third one is a Pink-toed Tarantula (Avicularia sp., perhaps A. urticans). I don't know what the other two are.

Wax-tailed Planthoppers (family Fulgoridae) have bizarre waxy trailers that are used to redirect predators away from the more important parts (head, body). This one is a Red-dotted Planthopper, Lystra lanata.

Mantises are so diverse and plentiful in this area that at least one group of mantis specialists have visited these same camps (they preceded and slightly overlapped us last year). However, I only saw a few mantises this year. This tiny one made some floating vegetation on the river its home.

Kevin spotted this well-camouflaged bark mantis, Liturgusa sp.

By far my favorite mantis this year was this leaf mimic, Acanthops sp.

This five- or six-inch centipede was devouring a small frog.

This wasn't a particularly attractive planarian, but it was a planarian, and one does not see a planarian every day.

Amazonian invertebrates must beware of the Cordyceps fungi, which kill their hosts from the inside and then grow out from the bodies of the deceased. This one used to be a moth.

I think this one used to be a caterpillar.

Occasionally we'd come across a roosting bird at night. The only ones I got pictures of are apparently manakins, but Matt and I did find a roosting toucan, which flew off before we could get any photos.

I think this nesting one is a Green Manakin, Xenopipo (Chloropipo) holochlora.

And I think this one is a Blue-backed Manakin, Chiroxiphia pareola.

In the mammal department, we saw a number of cute little Tree Opossums (Marmosa sp., perhaps M. murina). They have crazy long tails and are not as skittish as your typical small mammals. I saw one larger opossum and one armadillo as well, but they were less cooperative than the tree opossums.

Nighttime Lizards

Surprisingly, Thecadactylus solimoensis is the only native nocturnal gecko in the area. In addition to the one pictured above from the Madre Selva bathroom building, I also saw one patrolling my tambo at night. And I actually saw one in the forest this year (found, as was so often the case, by Edvin).

Occasional Gymnophthalmids scuttled about in the leaf litter at night. I believe this one is a Black-bellied Forest Lizard, Alopoglossus atriventris.

Other than the Thecadactylus and Gymnophthalmids, all of the numerous lizards I saw at night were diurnal species trying to get some rest. It was definitely easier to find most diurnal lizard species at night than during the day.

Anoles were the most plentiful of these sleeping lizards; on a typical night I'd see between 2 and 10 anoles sleeping on leaves or twigs. Three small, basically brown species can be hard to distinguish. The most common were (of course) the Common Forest Anole, Anolis trachyderma, which I think these two are.

Female Slender Anoles, Anolis fuscoauratus, have a wide, straight-edged vertebral line with dark edges. That's what I think these two are.

The third of the small basically-brown anole species is the Amazon Bark Anole, Anolis ortonii. They have a more mottled pattern than the other two similar species. That's what I think these two are. (But maybe they are male A. fuscoauratus instead?)

Banded Tree Anoles, Anolis transversalis, would never be confused with the three small brown species.

A few of the diurnal geckos would sleep in plain sight, such as this Collared Forest Gecko, Gonatodes humeralis.

Last year I saw only one Amazon Forest Dragon, Enyalioides laticeps, which was a very small juvenile sleeping at night. This year I saw a bunch of them of various sizes. None were quite as small as last year's, and none were the really big dramatic-looking males. But they are still some pretty fine lizards.

Last year I saw two sleeping Olive Tree Runners, Plica umbra ochrocollaris, but neither was in a position for a good in situ photo, so I came away with lousy pictures. This year I saw four or five, of which three were cooperative. (I also saw one Collared Tree Runner, Plica plica, at night, but it clambered up the tree upon which it was spread-eagled before I could get a photo.)

Nighttime Amphibians

Nighttime is frog time in the rainforest. You couldn't always expect to find snakes, but you could always find some frogs.

Some of the diurnal species could be found at night. This Sharp-nosed Toad, Rhinella (Bufo) dapsilis, did its best treefrog impression perched on a leaf a couple of feet off the ground.

Despite its name, the diurnal Common Harlequin Toad, Atelopus spumarius, is a difficult species to find in general, as are most species in this troubled genus. Last year we found a few by day when searching in the one particular area at Madre Selva known to support a population. This year I didn't see any by day, even though I searched in the right area for some time. This one was found at night by Edvin.

Probably the most numerous forest-floor frog species was the Common Big-headed Rain Frog, Oreobates quixensis.

Pristimantis is a large genus of small frogs. Many of the species have confusing and overlapping diagnostic characteristics, and a confident ID often requires examining the thigh color, belly color, and various subtleties of shape and pattern. In most cases I took photos in the forest, often without touching or moving the animal, so even though I got some advice from Dick Bartlett and others, I can't be completely confident in many of the IDs. I'll give my best guesses; please let me know if you can help with the IDs.

I think this is Pristimantis academicus, a recently-described species, based on the lumpy orange/brown blotches. It looks diseased, but so do the (few) other pictures of P. academicus that I've seen.

I think this is an Amazonian Rain Frog, Pristimantis altamazonicus, based on the pattern and orange-red & black flash marks on the thighs.

I'm reasonably confident that this is a Long-nosed Rain Frog, Pristimantis carvolhoi.

This one seems likely to be a Santa Cecilia Robber Frog, Pristimantis croceoinguinis.

And this one looks like a Diadem Rain Frog, Pristimantis diadematus.

This one, which has chosen an uncomfortable perch, looks like a Striped-throated Rain Frog, Pristimantis lanthanites.

This one looks like the unimaginatively named Malkin's Rain Frog, Pristimantis malkini.

This happy couple appears to be a pair of Carabaya Rain Frogs, Pristimantis ockendeni.

Finally I have a few Pristimantis for which I haven't been able to come up with even a reasonable guess. This one looks kinda like Pristimantis peruvianus and kinda like Pristimantis conspicillatus and probably kinda like half a dozen others.

Last year I photographed a frog that looked pretty much just like this. At the time Dick Bartlett suspected it was a juvenile that was young enough that it hadn't developed its distinguishing characteristics yet. Now I've seen another, extremely similar individual, but I still have no idea what species it might be. (The "W" shape on the shoulders is a clue, but many Pristimantis species have that mark.)

And one more completely unidentified little Pristimantis. This one has fairly evenly spaced pointy tubercles all over its body. Guesses are encouraged!

Here's a small frog that is easy to identify. This is a Bassler's Sheep Frog, Syncope (Chiasmocleis) bassleri.

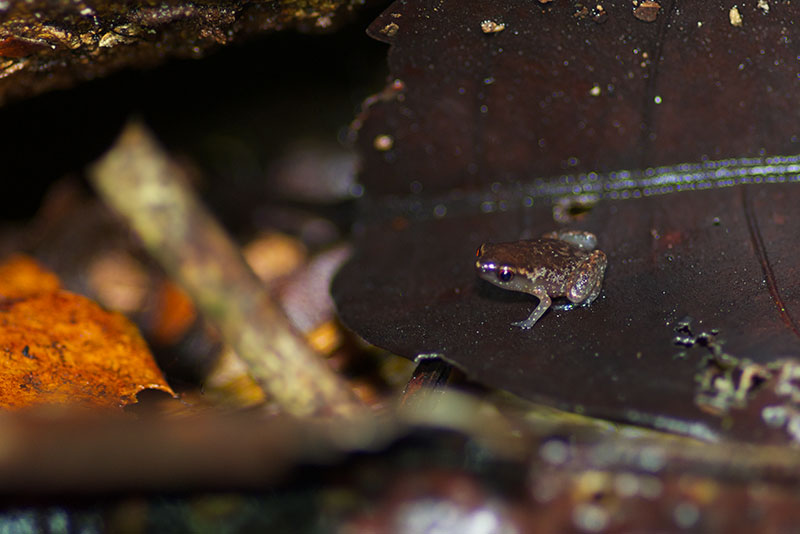

At first I thought this extremely small frog (perhaps 1/4 inch long) was a tiny baby Syncope bassleri, but the pattern and colors didn't seem quite right. I now suspect that it is instead a Dusky Pygmy Sheep Frog, Syncope antenori.

This little guy is either a Cocha Chirping Frog, Adenomera andreae, or a Forest Chirping Frog, Adenomera hylaedactyla. I saw it in the forest rather than in an open area, and I estimate that the distance from the eye to the tip of the snout is closer to 1.5x the eye diameter than it is to 1x the eye diameter. According to my references, that means it is probably A. hylaedactyla.

You could tell whether a night was going to be particularly froggy by the number of "Whooooop!" calls made by huge Smokey Jungle Frogs, Leptodactylus pentadactylus. It turns out that if you photograph them from the front, their eyes don't necessarily shine red the way they do if you photograph them from the side.

The closely related Sharp-nosed Jungle Frog, Leptodactylus bolivianus, can be distinguished by its, well, sharp nose, as well as the light line above its lip.

One night we took a boat out to a cocha (lagoon) on the river to look for tree boas, caimans, and frogs. We saw no tree boas and no caimans on that particular night, but we did see this cute little Spotted Hatchet-faced Treefrog, Sphaenorhynchus dorisae. The "treefrog" part of its name is a bit of a stretch, as they are live nearly aquatic lives in floating vegetation.

A more typical treefrog species, the Two-striped Treefrog, Scinax rubra, is quite variable in pattern and color. These two individuals were found a few feet from each other.

This year I really wanted to see a Fringe-lipped Treefrog, Scinax garbei, a species that I had not seen last year, because I have a particular fondness for excellent camouflage. Matt told me where to look for them at Madre Selva, and I spent half an hour or so poking around in the right area before I discovered this fine fellow hunkered down on a leaf about six feet off the ground.

The genus Hypsiboas was split off from Hyla not too long ago, and contains a number of mostly-larger treefrog species. This smallish (for Hypsiboas) one is Hypsiboas (Hyla) nympha, for which I've not found any English name.

Rocket Treefrogs, Hypsiboas (Hyla) lanciformis, are fairly large, pointy-snouted frogs that can leap a tremendous distance. Last year they were quite common. This year I didn't think I had seen any, but when I looked through my photos after the trip I realized that I had in fact photographed one (at the time I had thought it was an Osteocephalus, since we were seeing many of those).

Map Treefrogs, Hypsiboas (Hyla) geographicus, have elaborate blotchy patterns on their backs, and neat reticulated eyelids that are visible when they sleep.

This greenish treefrog is either a Buckley's Slender-legged Treefrog, Osteocephalus buckleyi, or a Forest Bromeliad Treefrog, Osteocephalus cabrerai. Dick Bartlett thought it looked like the former, so I'm going with that.

Several Osteocephalus species in the area are difficult to distinguish. I think the following are all Osteocephalus yasuni, due to the strong yellow coloration, relatively small tympanums, white upper lips, and reticulations rather than radiating lines in the irises.

These two I've also tentatively identified as Osteocephalus yasuni, due to their relatively small tympanums, white upper lips, and reticulations rather than radiating lines in the irises. But they don't have any of the usual yellow coloration of that species, so I'm not too confident.

I'm guessing that this one is a Mocking Bromeliad Treefrog, Osteocephalus deridens, due to its relatively small tympanum, overall smaller size, and radiating lines rather than reticulations in the iris (hard to see except in the full-resolution original photo).

The only photo I've got of this one doesn't show the eyes or front of the head clearly, which makes it extra hard to identify. It might not be an Osteocephalus at all; it could be Hypsiboas lanciformis. But Dick Bartlett thought it looked most like the Common Bromeliad Treefrog, Osteocephalus leprieurii, so that's my best guess.

Finally, a trio of what I believe to be Flat-headed Bromeliad Treefrogs, Osteocephalus planiceps. Distinguishing characteristics include large size, white upper lips, relatively large tympanums, and radiating lines rather than reticulations in the irises (though the tympanum on the third one seems suspicously small). Each of them is in the traditional "I'm about to leap really far away from you" pose.

Looking for salamanders in Amazonia is not at all like looking for salamanders in the U.S.A. In Amazonia one looks for salamanders perched on leaves at night, often nearly vertical leaves. I've tentatively identified these all as Amazon Climbing Salamanders, Bolitoglossa altamazonica, though possibly some or all of them are other Bolitoglossa species.

Nighttime Snakes

As I mentioned before, I only saw one snake in the wild during the day. And the snake-viewing was also slow the first two or three nights. But then it picked up nicely, and I ended up seeing 29 snakes of 17 different species. (This only counts the ones I saw while they were still wild or within a few moments of being captured; there were plenty of other snakes seen by others, and still more brought into camp by local villagers.)

Like last year, the most commonly-seen snake was the wonderfully thin and strong Common Blunt-headed Tree Snake, Imantodes cenchoa. I saw 10 of these snakes overall.

The snail-eating snakes in genus Dipsas have the same basic body plan as Imantodes, but less exaggerated. They are long and thin and graceful, but not that long and thin and graceful. We saw two species. The Ornate Snail-eating Snake, Dipsas catesbyi, is the prettier one.

The Big-headed Snail-eating Snake, Dipsas indica indica, is neither as pretty as Dipsas catesbyi nor as long and thin and graceful as Imantodes cenchoa. But it is a fine snake nonetheless. I don't want you bad-mouthing it.

The Red Vine Snake, Siphlophis compressus, is another nocturnal arboreal specialist. When Edvin found this one on our first night out hiking, we thought he called it the "Red Wine Snake", and for awhile we were inventing interesting backstories for that sadly misunderstood or misspoken name.

In addition to the Oxyrhopus vanidicus pictured earlier, we also found the other two Oxyrhopus species that live in this area. This Yellow-headed Calico Snake, Oxyrhopus formosus, was stretched across a branch directly over the trail, about ten feet up.

This juvenile Banded Calico Snake, Oxyrhopus petola digitalis, seemed to be in an ambush position on a leaf close to the ground. But maybe it was just in an "if I hold perfectly still nobody can see me" position.

The Atractus genus of leaf-litter snakes holds many confusing species, probably including several undescribed ones. I only saw one individual, and fortunately it was one of the easier species to identify. This is the hyperbolically named Big Ground Snake, Atractus major. It is not big. The first photo is in situ, before it was captured to bring back to camp for photos; the second photo is the same snake the next day, when it was released from its detainment.

As with the anoles, it was easier to find diurnal snakes sleeping at night than it was to find them active during the day. This one is an adolescent Glossy Forest Racer, Drymoluber dichrous. Adults are patternless and youngsters have strong banding; this one is in between.

This Olive Whipsnake, Chironius fuscus, was coiled high in some branches overhanging a stream. After I took this photo, we tried to capture the snake, and very nearly did so. A couple of us maneuvered the branch such that the snake started crawling, and a couple of us positioned ourselves at the edge of the embankment to try to grab it when it got close enough. Two of us managed to touch it, but not quite to grab it, and it slipped free and fell/dove into the stream. We waited, watched, and poked with tongs, but didn't see it again. We told Edvin, who had first seen this one, that he would just have to find another one for us. He laughed, and then found another one about two minutes later. All hail Edvin!

Will found this small Green-striped Vine Snake, Xenoxybelis argenteus, after not only Edvin, but also Cesar, Segundo, and Julio had passed right by and missed it. Will slept well that night.

Alas, we found no Bushmasters this year. Our consolation prize was a quartet of coral snake species. Here they are in order of how often they have been seen by Matt in his many trips to this area, from most often to least often.

Aquatic Coral Snake, Micrurus surinamensis. This beautiful snake is generally one of the most commonly seen snakes on these trips. As a group we saw four or five on this trip, which is less than usual. The photo was taken where the snake was found by Matt, after it became aware of our presence and flattened its body.

Western Ribbon Coral Snake, Micrurus lemniscatus helleri. I think this was the only one we saw as a group this year. Last year we saw three or four, which I think is more typical. I tried to get photos of the snake in the forest where it was found, but at the time it was very unhappy about having been dug out of a mudhole, and was thrashing around in a very unphotographable way. This photo was posed the next day. (As you might have been able to guess, I don't have very much patience for the posed photos, and often end up with mediocre ones like this.)

Sooty Coral Snake, Micrurus putumayensis. This was only the second one Matt had ever seen, and the first one was a seriously ill specimen many years ago. This was the best snake of the trip for a few days. This photo was taken in the forest a few feet from where the snake was found.

Langsdorff's Coral Snake, Micrurus langsdorffi. This was the first one Matt had ever seen, and immediately took over the ranking of best snake of the trip. This species is highly variable in pattern, even within a population. This species with this particular pattern, lacking black rings, is rare and beautiful enough to be the cover snake of Campbell and Lamar's "The Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere" (volume 1). Edvin found this snake right at dusk very close to camp on our first day at Santa Cruz. He brought it over to the open area for us all to admire, where we took photos. (Other folks took more photos the next day, also.) If I remember correctly that is Kevin's gloved hand carrying the beautiful serpent.

Finally (and this is, I promise, the final time I will start a sentence with the word "finally" in this post), here's one more group shot. This one includes the crew members that accompanied us at both Madre Selva and Santa Cruz, except for Cesar, who was kind enough to take the photo.

Front row, left to right: Edvin, Rebecca, Segundo.

Back row, left to right: Matt, Lorrie, Kevin, John (me), Bob, Will, Pepe (cook, yum!), Rick, Emerson.

John