The roster for this trip included such familiar names as Dick Bartlett, Pat Bartlett, Lorrie Smith, Mike Pingleton, Karl Switaki, Bob Applegate, and many others. (Dick and Lorrie are co-owners of MT Amazon Expeditions.) I knew of many of these fine folks from various books, fieldherpforum posts, email exchanges, etc., but I had never met any of them in person before. So I got to significantly expand my life list of herpers as well as my life list of herps.

Road cruising, Iquitos style

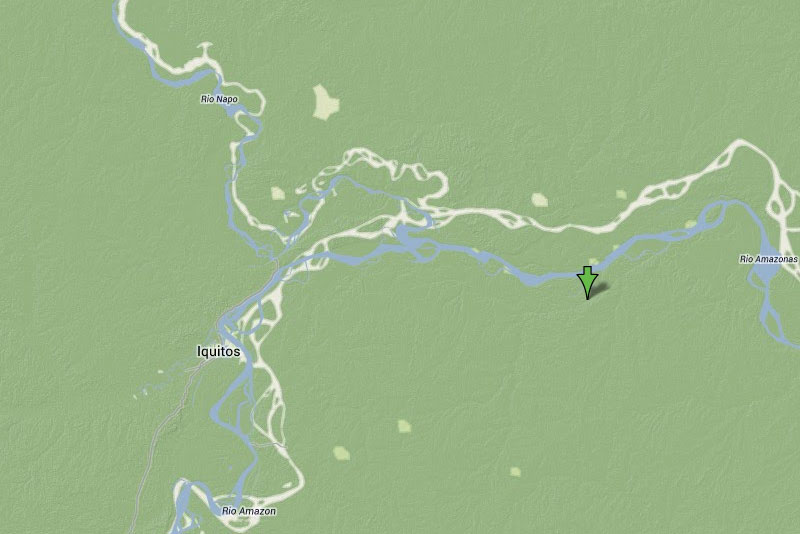

We started by gathering in Iquitos, the launching point for Amazonian travel in Peru. Iquitos is hiding under the red pointy thing on this map:

Iquitos is the largest city in the Peruvian rainforest, famous for being the largest city in the world unreachable by road. That is true, unless you happen to be starting in the town of Nauta, about 60 miles south of Iquitos. A road connects Nauta and Iquitos, and Matt had arranged for a local driver with a van to take some of us road cruising on that lonesome road on our one night in Iquitos before heading off to the rainforest preserves. He had seen a big boa constrictor on that road on his previous trip, among other goodies.

The driver didn't speak English, so we also had along a bilingual MT Amazon Expeditions employee whose job it was to tell the driver when to speed up, when to slow down, and when to stop, relaying and translating these requests from Matt and, to a lesser extent, everyone else. The driver was mysteriously unfamiliar with the concept of road-cruising for herps, and it took repeated and vociferous convincing to get him to speed up through the more inhabited parts of the road near town, and slow down in the wilder parts of the road further out. There had been very little rain recently, so the road was almost entirely dry, not a good omen for tropical herping. Maybe the moon was in the wrong phase also, or maybe we had eaten cursed noodles at Ari's Burgers in town, because the herps were scarcely moving at all. Two DOR water snakes were all we had to show for the first hour or so. We eventually found a few frogs, and stopped awhile for pictures.

Rough-skinned Green Treefrog (Hypsiboas cinerascens)

Polka-dot Treefrog (Hypsiboas punctatus)

Two-striped Treefrog (Scinax rubra)

On the way back we did find one actual live snake, a crazily long and thin Blunt-headed Tree Snake (Imantodes cenchoa) that had decided to become terrestrial for awhile. I didn't get any photos of this snake, but perhaps more will appear later in this story.

Shortly after the Imantodes perked us up a bit we were further intrigued by a weird-looking beast in our headlights walking on high, stiff legs straight towards us. I (and at least one other person, so I'm not totally insane here) at first thought it was a very large toad, before someone shouted "caiman!". Apparently that is a synonym for "stop" in Spanish because the driver did just that very quickly. Even more quickly, an intrepid herper had leapt from the van, raced to our new-found friend, and detained it with one arm around the neck and another around the waist. The caiman seemed shocked into a frozen state by this unexpected infringement of its personal freedom, and placidly let several of us hold it for awhile and admire it up close. This was a Smooth-fronted Caiman (Paleosuchus trigonatus), a good species to see on this road because it is rarely found in the rainforest near big rivers where we'd spend the rest of our trip.

Here's a happy Matt with an equally smiling but decidedly less happy caiman:

Now Mike Pingleton is a frog guy at heart, and while he enjoys seeing a beautiful caiman as much as -- or dare I say even more than -- your typical person on the street, he's not one to stand around watching different people hold the same crocodilian when there might be frogs to be found. So he wandered over to a nearby pond edge and started looking around. Meanwhile, an intrepid herper decided that it was time to get some naturalistic photos of the caiman, and gently placed it atop a conveniently located log. The caiman continued its shocked-into-submission act, droopily squatting on the log most unphotogenically. When a salamander behaves so, what does a photo-desiring herper do, but try to tickle it with a tiny twig so that it lifts its head to look proud? And really, when you get right down to it, what is a caiman if not a big salamander with rougher skin? So if an intrepid herper were to pick up, say, a six-inch twig, and use that in an attempt to prod a caiman into a nicer pose, that would be a sensible idea, right?

Hmm, maybe not.

While our intrepid herper's deeply bitten hand was being wrapped with makeshift bandages, the no-longer-frozen caiman strutted about menacingly for awhile, safe in the knowledge that it was highly unlikely that anyone else was going to be trying to pick it up or otherwise manipulate its position anytime soon.

The caiman excitement over, I joined Mike to check out the frogging situation. There were at least three species occasionally visible, but I only got photos of two of them.

Variable Clown Treefrog (Dendropsophus triangulum)

Greater Hatchet-faced Treefrog (Sphaenorhynchus lacteus)

We poked around at the pond edges admiring the anurans for another twenty minutes or so. Eventually someone decided that all things considered it was probably in our best interest to consider tapering off our gentle meanderings in froglandia so that the intrepid herper could get to a medical clinic to have that hand looked at. (As it turned out, several stitches were involved, but there was no serious damage.) Also, we had to get up early to catch our boat ride down the river.

Down the Amazon

Usually MT Amazon Expeditions trips downriver involve a stately cruise on a roomy boat where travelers can mingle and get to know one another while enjoying a tasty meal. However, that boat was being refitted with a refurbished engine and was thus unavailable, so instead we hopped onto a not-so-roomy speedboat and jetted off down the Amazon towards our forest destination. On the bright side, we reached the herp-filled forest more quickly than we would have otherwise. We were hoping to see Caiman Lizards along the river or on floating logs, as the previous year's group had, but no such luck this time.

Madre Selva and Santa Cruz

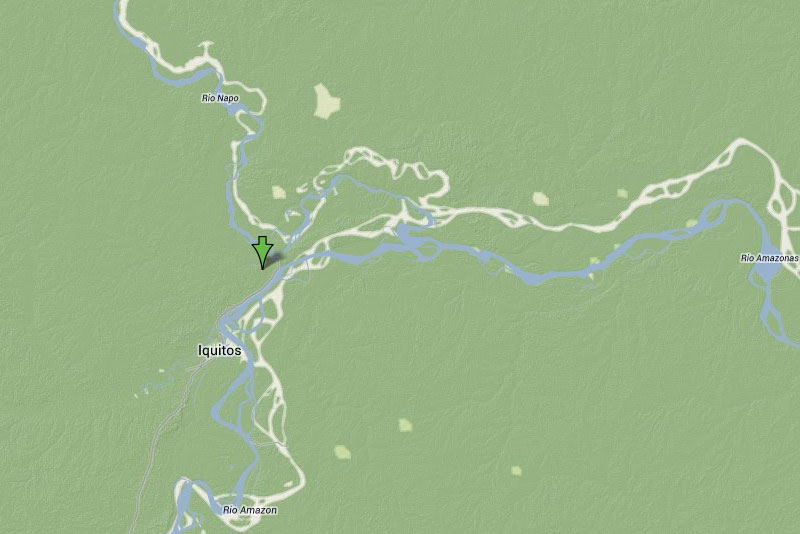

We spent the first part of our trip at Madre Selva Biological Station, a forest reserve managed by a non-profit organization named Project Amazonas that is affiliated with MT Amazon Expeditions in an intertwingled way that I still don't fully understand. Madre Selva is here:

We spent the second part of our trip at another Project Amazonas location, Santa Cruz Forest Reserve. It is closer to Iquitos as the toucan flies but still remote and wild. It is far enough from Madre Selva (and on the other side of the Amazon) that it has a significantly different species distribution, though the two places have many species in common. Santa Cruz is here:

Each camp had a generator, which would run for a few hours around mealtimes; at other times there was no electricity. We slept on cots with mosquito nets. Separate bathroom buildings housed sinks and toilets, and cold showers with water pumped up from the river (so you definitely wanted to keep your mouth shut while showering).

The fixed points in our daily schedule at each of the two reserves were the three important ones: breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Good, sometimes delicious, food was prepared and served by local staff members. Since there were no other options for eating, you didn't want to miss the mealtimes.

Here are a few photos of the camps, to give you a flavor of the conditions.

Some of the individual huts, called "tambos", at Madre Selva. One or two people stayed in each of these:

The Madre Selva "bachelor pad tambo", where I and six other men enjoyed camaraderie and the occasional nighttime menacing rat visitor:

At Santa Cruz the tambos were arranged around a grassy open area:

Group shot of the travelers and local staff:

The villagers near Madre Selva had learned over the years that when a herping group was encamped, they could trade captured forest critters for T-shirts, hats, and other useful items; we had all brought along this kind of booty in preparation for such trades. These animals, mostly but not always herps, would be kept around for a day or so for photographs, and then released in appropriate habitats. They joined other animals captured by our group, so that at any given time there would be quite a menagerie in ziploc bags, cloth sacks, and jars. Each reserve had an area set aside for storing and photographing these animals. At Madre Selva it was an entire building known as the photo hut. Santa Cruz didn't have an entire building to spare, so an area of the main building was used for this purpose, while another area was used for dining, and still other areas used to squeeze in some sleeping spots since there weren't quite enough tambos to go around.

A couple of village children waiting outside the Madre Selva photo hut while their offerings are evaluated

Dick Bartlett with a cute little possum, on the steps of the Madre Selva photo hut

Villagers brought in quite a few interesting animals that we didn't otherwise find in the wild. And each time one or three of us would go out searching in the forest, we were likely to encounter, and often bring back, some species that others in the group had not yet seen. So at pretty much any time you could go into the photo area and take your pick of many species that were new to you. Here's a couple of my favorites:

Common Monkey Lizard (Polychrus marmoratus). This beautiful adult was brought in by a village child. We didn't see any others on this trip.

Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus murinus). This smallish specimen, maybe four feet long, was brought in by a fisherman. We didn't see any other anacondas either. Dick and Lorrie disparaged the general unattractiveness of this one, but this is the closest I've been to seeing a wild anaconda so I wasn't complaining:

It would have been possible to spend all day every day doing nothing but photographing captured animals, and many people spent long hours in the photo hut setting up and taking beautiful photographs on naturalistic tabletop setups. I joined in a little at first, but the call of the forest soon pulled me away, and I ended up spending pretty much all of my non-eating, non-sleeping time hiking in the forest and taking photos there, sometimes with two or three other people, and sometimes by myself. All of the rest of my photos are of animals I personally saw in the wild. I got in situ shots wherever possible, but would detain critters in the forest to get better photos when necessary.

A welcome camp visitor

At our first lunch at Madre Selva, I was chatting with Matt about how my beloved manual Pentax 200mm macro lens had developed some sort of light leak that caused most photos to be significantly overexposed. By a happy coincidence, he had brought along a 100mm macro for his Pentax, which camera he carried only as a backup in case something terrible were to happen to his Canon. And being an incredibly generous guy, he volunteered to lend me his lens for the duration of the trip. So after lunch we were walking together up the little camp path towards the tambos when something very large caught our eyes as it strolled across the path in front of us. Caiman Lizard! Matt's instincts were quicker than mine and he dove in the direction of the massive saurian, just missing it as it crashed into a thick strip of jungly vegetation. Matt shouted out "big lizard!" to get some help, and several more post-lunch wandering herpers hurried over. We spread out along all sides of the strip of vegetation, and also blocked the possible escape route into the forest proper. Matt and Jake Scott bushwhacked their way in, near where the lizard had entered, and thomped around to try to spook it out. After a few minutes of this, the lizard made its move and dashed from its hiding place into the waiting arms of one of the camp staff. Being familiar with the local fauna, he grabbed it firmly behind the head, giving it no opportunity to bite -- these lizards crush rock-hard aquatic snails with their massive jaws. Some of us took turns holding it, then we posed it for pictures (though considerably more carefully than our intrepid herper had posed the caiman on Nauta road), and later that afternoon released it into the water.

Jake and our favorite camp visitor, a Northern Caiman Lizard (Dracaena guianensis). Jake's first reaction when he actually saw the beast was "When you shouted 'big lizard!', I didn't realize it was THAT big."

Perhaps it's blushing with embarrassment about being caught by a bunch of clumsy humans

Off to tell its friends never to visit this particular spot again

Hiking in the forest

Each of the two reserves had a network of hiking trails of various lengths. You could choose a half-mile trail for a quick excursion, or a five-mile trail on which to hike all morning or all afternoon, or late into the night. Or you could go back and forth on a half-mile trail, and see different things on every pass. Most of the trails were fairly level, though there were exceptions. Many of the trails crossed creeks and streams of various sizes.

Six legs, eight legs, no legs, etc.

Let's get it over with: Amazonia is full of bugs. Mostly mosquitos and ants, it seems, but also a zillion kinds of spiders, scorpions, grasshoppers, katydids, butterflies, moths, etc. etc. Here are a few of my favorites from this trip:

Leaf mimic katydid (Typophyllum sp.)

Tailless whip scorpion (Heterophrynus sp.). These guys look vicious but they neither sting nor bite (people, anyway). They're also unreasonably fast.

Planarian. Not unreasonably fast.

Tiger beetles in an orderly nocturnal cluster.

Pink-toed Tarantula (Avicularia sp., perhaps A. urticans).

Insect assemblage: Mating assassin bugs, one of which is feeding on some other bug, which is also being picked over by at least five flies of at least two species. And there are also at least two small flies on the larger assassin bug.

Dead-vegetation mimic mantis (Acanthops sp.)

Ex-weevil, devoured by Cordyceps fungus

Frogging by day

Somewhere I read that this area of Peruvian Amazonia has more anuran species than anywhere else in the world. Maybe that's true and maybe it's a slight exaggeration, but in any case there are gobs and gobs of different frogs and toads. I personally saw about 40 species in the wild, and our group as a whole saw about 60 species, and there are many that we missed out on, plus new ones being described frequently. Most of the frogs and toads come out at night, but there are still plenty to see in the daytime.

The most common diurnal forest floor hoppers are toads in the species complex Rhinella "margaritifera", called Crested Forest Toads or South American Common Toads. Befitting their status as a confusing group of similar toads, these come in a bewildering variety of shapes, patterns, and colors.

One species that we saw has been successfully extracted from the "margaritifera" species complex. This is a Sharp-nosed Toad (Rhinella dapsilis). Its fleshy snout appendage and relatively smooth skin distinguish it from the who-knows-how-many other species that are still grouped together until some herpetologist puts in the time to figure them out.

Another group of day-active frogs in Amazonia are the Dendrobatids (Poison Frogs). As a group we saw four species, but I only saw two of them in the wild. The first was the quite common Pale-striped Amazon Poison Frog (Ameerega hahnelli), a few of which could usually be stumbled across each day.

Much more eye-catching was this tiny Duellman's Poison Frog (Ranitomeya duellmani), no more than half an inch long. It leapt about like mad for several minutes, never sitting still long enough for a photo but also never leaving a fairly small area. I'd see it hop, take a few seconds to relocate it in the dim forest light, and re-aim my tripod, only to have it hop again. After playing this game for awhile it did eventually settle down, and I got a few photos.

Competing with the Ranitomeya for the title of Most Beautiful Frog in the Forest was the Common Harlequin Toad (Atelopus spumarius). This is a troubled genus throughout much of Central and South America; they have disappeared or become vanishingly rare in many locations where they were once abundant. Matt knew of one particular location in Madre Selva with a population of these toads, and we were successful in finding them there on a couple of occasions.

Dick Bartlett knows the frogs of this area better than nearly everyone in the world, but even with his help not all of the frogs I ran across could be identified. This was especially true for frogs that I only took photos of in situ; without examining their bellies/underarms/chins/teeth/etc. Most of these were in the large and confusing genus Pristimantis, which was fairly recently split from the even larger and more confusing genus Eleutherodactylus. Most Pristimantis were active only at night, but I got photos of at least two interesting-looking species by day that couldn't be identified by me, or Dick, or some Peruvian amphibian specialists to whom Dick sent the photos.

This one was extremely lumpy, with an orange crown that broke up its froggy outline so well that each time it hopped it would take me quite a while to make out its shape again, even though I was staring right at it the whole time. It looks somewhat like P. carvolhoi, but according to Dick and associates it is not that species. It might be an undescribed species.

This one had distinctive yellow spots atop both the fore and hind limbs, which is something Dick and the Peruvian amphibian specialists did not recognize. It too might be an undescribed species.

Diurnal herps that were not frogs

There were a decent number of diurnal lizards in the rainforest, though nowhere near as many individual lizards as you'd see in, for example, a good desert habitat. Perhaps the most commonly seen were a couple of Gonatodes geckos. The more disturbed and open areas of the forest were the lair of Bridled Forest Geckos (Gonatodes humeralis).

Trees and branches deeper in the forest held Collared Forest Geckos (Gonatodes concinnatus).

Scattered through the forest was an occasional anole. It was quite a contrast from South Florida or the Caribbean, where anoles are everywhere in large quantities. We probably saw more anoles asleep at night than out and about during the day, and we didn't see *that* many anoles asleep at night.

The anole I saw most frequently was, appropriately enough, the Common Forest Anole (Anolis trachyderma):

My favorite anole by far was the Blue-lipped Forest Anole (Anolis bombiceps), which had fantastic leaf-litter camouflage:

Competing with A. bombiceps for best leaf-litter camouflage was the aptly named Western Leaf Lizard (Stenocercus fimbriatus), in the family Tropiduridae. These lizards were reasonably common, but had such great camouflage that you had little hope of seeing them unless they moved, which they usually did only when running far away.

The other tropidurids I saw were tree runners. There were two species locally, but the only one I saw during the day was the Collared Tree Runner (Plica plica), whose scientific name is so fun to say, over and over. These largish lizards were flat, great climbers, and fast -- sort of the Amazonian tree version of the Banded Rock Lizards (Petrosaurus mearnsi) of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park and suchlike places.

Light gaps in the forest, typically around recently-fallen trees, were a popular hangout spot for Black-spotted Skinks (Copleoglossum nigropunctatum).

A couple of species of whiptail lizards were around, but as with most whiptails they did not generally sit and pose for photos willingly. I only managed to get photos of one individual, a Forest Whiptail (Kentropyx pelviceps).

Impressively large Golden Tegus (Tupinambis teguixin) could frequently be glimpsed dashing across open areas and even more frequently heard crashing through the brush. I never managed to capture one with my camera, though.

An interesting group of small (mostly) diurnal lizards were the microteiids in the family Gymnophthalmidae. To me they seemed like a cross between tiny whiptails and tiny skinks. Some of them were associated with streams, whereas others were in the dryer parts of the forest. They tended to be very elusive, but every once in awhile one would hold a position long enough to be photographed.

Elegant Eyed Lizard (Cercosaura argulus):

Black-striped Forest Lizard (Cercosaura ocellata bassleri):

As is so often the case, snakes were less numerous and less easily found than frogs or lizards. And most of the snakes we saw, we saw at night. But I did see a few during the day. A couple of them snuck away quickly without being photographed or grabbed, including one large Common Bird Snake (Pseustes poecilonotus).

I found this beautiful snake in the first fifteen minutes of my first morning on the trails, leading me to believe that I'd be finding snakes every fifteen minutes all day long. Not. This is a green phase Velvety Swamp Snake (Liophis typhlus typhlus):

Jake Scott wrangled this annoyed Common Whipsnake (Chironius exoletus) out of a tree just before Pat Bartlett and I caught up to him on the trail. We eventually got it to sit still for a few seconds at time. No doubt it was only pausing to consider the best way to bite us and then speed off. It did actually bite me a few times as I prevented its exit, but its bite was very mild, not even breaking the skin. (And yes, this picture was taken during the day. Much of the rainforest floor is a dark, dark place.)

Paddling the Rios

At Madre Selva a few kayaks were available for relaxing river excursions. One fine morning Mike Pingleton and I went for a paddle. We and the kayaks were speed-boated up the Rio Orosa -- the tributary along which Madre Selva is situated -- and across a small channel to the Rio Amazonas itself, where we were set free. This allowed us to return by padding our kayaks only downstream (I did note that the river excursions were relaxing).

Mr. Pingleton, looking decidedly unstressed:

A Pink-toed Tarantula apparently waiting for something interesting to climb out of the river

View from the kayak towards the channel short-cutting from Rio Amazonas to Rio Orosa

After drifting, er, strenuously paddling across the channel, Mike and I took opposite sides of the Rio Orosa to maximize our chances of seeing interesting wildlife. I mostly kept my eyes scanning along the vegetation right at the river's edge. Suddenly something clicked in the pattern-recognition part of my brain: had there been an unexpected shape atop that hunk of log suspended in branches that I had just drifted past? I was now too far away to tell, so I turned the kayak and paddled back in that direction. As I got closer, I was happy to confirm that the unexpected shape was in fact the shape of a lizard.

I shouted out across the river "Hey Mike, there's some sort of cool-looking lizard over here!", and he paddled with appropriate eagerness over in my direction. I recognized the lizard as teid-ish, but initially wasn't sure beyond that. We took turns getting nearer and nearer for photos. Eventually we filtered through our memories of pictures from guidebooks to conclude that it must be a Crocodile Tegu (Crocodilurus amazonicus), and indeed that's what it turned out to be. A juvenile, retaining the colorful patterns of youth. The lizard was remarkably cooperative. Both Mike and I got to within a couple of feet while it held its pose.

After we were satisfied that we had exhausted the photo opportunity, we decided to try to catch the tegu so we could bring it back for the rest of the group to admire. At that point I was closest to the lizard, so I drifted even closer, hoping it would sit still until I could make a grab for it. Mike said "Maybe I should try to get around behind it to block its exit route", but I judged that the lizard was getting a little nervous and would probably bolt soon, so I took one last paddle and leaned and stretched … and the tegu took three steps and then splooshed into the water, never to be seen again. Bummer!

Mike headed back over to the other side of the river, probably thinking well-deserved dark thoughts about my lizard-catching strategies and abilities. I was thinking those thoughts as well. I should have waited for Mike. Maybe the tegu would have been distracted by Mike enough that I would have had another instant or two to grab it. Now the other herpers will be sad; Crocodile Tegus are not often seen on these trips. As I was mentally bemoaning this fate, my eye caught some pattern in the water next to my kayak, and my left hand dropped the paddle and snatched something out of the river. An instant or two later my brain caught up to what my hand had done and I started laughing. I shouted out across the river "Hey Mike, I've got another one. And this one is in my hand." This one was smaller and even more colorful than the one that got away.

Neither Mike nor I had any bag to transport it back to camp, but with the mix of practicality and generosity for which he is rightly famous worldwide, Mike sacrificed one of his socks, into which the lizard was carefully placed, and in the knotted confines of which the lizard miraculously survived the short return journey. (Mike is not famous worldwide for the cleanliness of his Amazonian footwear.) I never did take a photo of my hand-caught and sock-transported Crocodile Tegu, but Matt got some beautiful ones, such as this:

photo above by Matt Cage

photo above by Matt Cage

Frogging by night

Once the sun sets (at 6:00, always at 6:00), the frogs really get going. First to be seen are often the toads, which provide some mild herping while you're walking from the dining area to wherever you put your camera and rubber boots. (I neglected to mention that one wears rubber boots all the time when hiking. They provide some protection from spiky plants, unfriendly ants, fer-de-lances, etc., and they keep your real shoes from being utterly destroyed by moisture and muck.) The main kind of nocturnal toad, and the only kind I got photos of, was the now-cosmopolitan Cane Toad (Rhinella marina).

A big one.

A bigger one. This one was so big that it didn't fit in the frame.

The most common forest floor toad-like hopper was not a Bufonid but rather a Strabomantid: the Common Big-headed Rain Frog, which was recently tragically reclassified to Oreobates quixensis from Ischnocnema quixensis, the older name of which is clearly funnier and thus better. We always enjoyed seeing one of these fairly goofy frogs, but I think part of our pleasure was just the opportunity to say "Ischnocnema!", a joy now lost to future generations of herpers.

When a medium to large anuran on the forest floor was not a toad or a Big-headed Rain Frog, it was usually one of the Leptodactylids. The really huge ones were Smoky Jungle Frogs (Leptodactylus pentadactylus), which have glowing red eyes because they are evil. Either that, or it has something to do with the way their eyes reflect light.

Almost as large, and with even beefier -- essentially Schwarzeneggerian -- forearms, was this Sharp-nosed Jungle Frog (Leptodactylus bolivianus).

Several medium-sized species were recently split out from the Leptodactylus "wagneri" complex, and they all look pretty similar, so I'm not completely confident in their IDs.

Dwarf Jungle Frog (Leptodactylus wagneri), probably

Peter's Jungle Frog (Leptodactylus petersii), perhaps

Smooth Jungle Frog (Leptodactylus diedrus), or so I have been told

One other Leptodactylid of note is the Painted Antnest Frog (Lithodytes lineatus), which appears to be a Poison Frog mimic.

Another distinctive leaf litter denizen is the mysteriously-named Amazon Sheep Frog (Hamptophryne boliviana).

Many leaves a few feet off the forest floor housed Pristimantis frogs of various species.

Santa Cecilia Robber Frog (Pristimantis croceoinguinis)

Peruvian Rain Frog (Pristimantis peruvianus)

Carabaya Rain Frog (Pristimantis ockendeni)

Green Rain Frog (Pristimantis acuminatus)

To keep this post from going on even longer, I left out a bunch of nocturnal Pristimantis of uncertain ID. You should thank me.

That leaves the treefrogs. So many treefrogs! I saw about twenty species, from itty bitty ones to monsters that barely fit in your hand. Here's an assortment of those, more or less in order of increasing size.

Many-striped Treefrog (Dendropsophus haraldschultzi). Aptly named.

Variable Clown Treefrog (Dendropsophus triangulum)

Clown Treefrog (Dendropsophus leucophyllatus). Some people consider this to be the same species as D. triangulum.

Forest Bromeliad Treefrog (Osteocephalus cabrerai). These had nice mossy camouflage colors.

Rocket Treefrog (Hypsiboas lanciformis)

Mocking Treefrog (Osteocephalus deridens)

Flat-headed Bromeliad Treefrog (Osteocephalus planiceps). These were relatively common, and usually seen in the "I'm just about to jump far away from you" pose.

I saved for last everyone's favorite group of Peruvian treefrogs: the monkey frogs, so named because of the way they walk on branches in lieu of jumping like sensible frogs. We saw three species. Here's a White-lined Monkey Frog (Phyllomedusa vaillanti) demonstrating the monkey walk, while a dragonfly larva holds its breath on the bottom of the branch.

The most beautiful of the three monkey frog species we saw was the Barred Monkey Frog a.k.a. Tiger Monkey Frog (Phyllomedusa tomopterna). They were a good deal too: two for the price of one!

And, last but most, the massive Giant Monkey Frog (Phyllomedusa bicolor). All three species of monkey frog could easily be found around a pond at the Santa Cruz reserve, but these were probably the most common of the three. They were certainly the most noticeable, and many individuals could be found in the same place each night. You could find them during the day napping very near the spot where you saw them calling the previous night. Here's one that hasn't yet awoken.

The same individual on the same palm frond, an hour or so later.

They looked particularly goofy when making their distinctive "bahb, bahb, bahb" call. Mike Pingleton decided that a particularly mellifluous individual deserved an appropriate name, and gave this weighty topic much thought before arriving at the perfect name: Bob. Heeeeeeeeeeeere's Bob:

Nocturnal herps that were not frogs

The armies of frogs did leave some room in the forest for other herps (many of which did their best to reduce the size of the armies of frogs). I'll save the snakes for last since herpers seem to have a disproportionate love for that particular branch of legless lizards.

I really really wanted to find a wild Amazonian salamander, and so was thrilled to notice this fairly small and drab Amazon Climbing Salamander (Bolitoglossa altamazonica) vertically adorning a leaf.

The pond that supported so many monkey frogs also contained a small population of Spectacled Caimans (Caiman crocodilus). They were easy to find via reflected eye shine at night.

Some of the Gymnophthalmid lizards were active both day and night. They were elusive little fellows, so I only got lame photos of wild ones just before they skittered off.

Black-bellied Forest Lizard (Alopoglossus atriventris)

Surprisingly (to me, anyway), there was only one species of nocturnal, arboreal lizard in the area. Conveniently, one prowled the walls of the bathroom building at Madre Selva. This is the Southern Turniptail Gecko (Thecadactylus solimoensis).

We did see plenty of arboreal lizards at night, though. Most were sleeping on leaves, twigs, or tree trunks, but a couple of them hadn't read the books, or perhaps just had a low reading comprehension level, because they were moving about. One such delinquent was a Slender Anole (Anolis fuscoauratus).

Another was a beautiful male Collared Forest Gecko (Gonatodes concinnatus):

The sleeping lizards represented a variety of families, including Dactyloidae, Gekkonidae, Gymnophthalmidae, Hoplocercidae, and Tropiduridae.

Common Forest Anole (Anolis trachyderma)

Amazon Bark Anole (Anolis ortonii)

Banded Tree Anole (Anolis transversalis)

Collared Forest Gecko (Gonatodes concinnatus)

Elegant Eyed Lizard (Cercosaura argulus)

Amazon Forest Dragon (Enyalioides laticeps)

Collared Tree Runner (Plica plica)

Olive Tree Runner (Plica umbra)

Some of the snakes we saw at night were diurnal and essentially terrestrial species that chose to spend their slumbering hours up high.

Velvety Swamp Snake (Liophis typhlus typhlus). These snakes come in an assortment of colors, to match any decor. Compare with the green one I saw by day.

Common Glossy Racer (Drymoluber dichrous)

As a group we saw quite a few of the local Helicops water snakes, but I managed to get a passable photo of only one wild individual. This is a Banded South American Water Snake (Helicops angulatus).

The most frequently seen snake, at least by me, was the Common Blunt-headed Tree Snake (Imantodes cenchoa). I needn't have fretted about not getting a photo of the one we saw crossing the Nauta road on our first night. I never grew tired of admiring these bulgy-eyed serpents with their mad balancing and climbing skillz.

I found one of these guys devouring its favorite snack, a presumably formerly sleeping Anolis trachydema.

One night we came across a much more rarely seen cousin, the Amazon Blunt-headed Tree Snake (Imantodes lentiferus).

One night a bunch of us took a boat ride to see what kinds of herps we could scare up on the river at night. Amazon Tree Boas (Corallus hortulanus) are often seen on these nocturnal water excursions, sometimes several per night. We only came up with one, which was low enough in the vegetation that Matt managed to wrangle it out of the tree and into the boat, all without anyone getting bitten. Here's a blurry picture from the back of the moving boat, just before the snake was snagged.

Since everyone loves beautiful things, and herpers love venomous snakes, it must be the case that herpers especially love beautiful venomous snakes. With that in mind, here's one of the most popular species we found in Peru: the Aquatic Coral Snake (Micrurus surinamensis surinamensis). These were almost as commonly seen as Imantodes cenchoa, but whereas to find that species you'd slowly scan the trees and bushes for a thin sinuous shape, to find this species you'd scan shallow creeks and their banks for crazy bright colors. Alternatively, you could just hike with Gina Harper, who would find them for you, typically right on the trail at your feet.

Here's one as found by one of the local guides using the more traditional shallow-creek-scanning technique:

And here's one as found by Gina using the more modern look-where-your-husband-and-his-friends-have-just-stepped technique:

When disturbed, these snakes jerk into a flat puffy posture, presumably to look bigger and thus more imposing. I guess this is for the benefit of stupid animals that aren't frightened off by the bright warning colors, such as herpers. Here's the same Gina-found snake a moment later, after the first few shutter clicks got its attention:

We saw another Micrurus species also, the Western Ribbon Coral Snake (M. lemniscatus helleri), but the only one I saw in the wild escaped before it could be photographed.

Shushupe!

On our penultimate night in the forest at about 1 in the morning I was sacked out on the floor in the main building at Santa Cruz, dreaming of the Bothriopsis vipers that we had hunted for in vain. I was jolted awake by the sound of the door being thrown open and an excited Matt Cage stating loudly, quickly, and calmly "Mike and I have a Bushmaster about halfway down the main trail. We need help." With that, he grabbed a pair of snake tongs and vanished back out the door.

Bushmaster! Everyone wanted to see a Bushmaster more than just about anything else, and nobody more so than Matt, who had been to this area umpteen times without yet seeing one. The others camping out in this room were Dick and Pat Bartlett, who not only had seen multiple Bushmasters before, but also would generally prefer that the younger folks do the late night running about on their behalf. Marisa Ai Ishimatsu was sacked out in a nearby room, and I knew that she was dying to see a Bushmaster, so after pulling some clothes and boots on and grabbing my camera and tripod, I ran back to Marisa's hideout and relayed the news. Then I rushed off to the main trail and headed down as fast as my clumsy rubber boots could carry me without sending me sprawling into the muck. On the way down I passed Travis Cossette, who was headed the same direction for the same purpose but considerably more carefully. The fool! There was a Bushmaster to see!

Perhaps half a mile down the trail I saw human figures in my flashlight beam. Mike and Matt were there, keeping a wary eye on the Bushmaster, which was a few feet off the trail keeping a wary eye on Mike and Matt. They explained that when they first saw it, it was coiled right on the trail, but when they had split up to get photos from different angles the snake had gotten spooked and started to crawl into the forest. Matt had gotten a snake hook on it for a moment, which was enough to cause it to stop crawling away and curl into a defensive posture instead. And there it still was, wondering what the heck had become of its peaceful night ambushing trail wanderers.

Amazon Bushmaster (Lachesis muta muta), coiled on the forest floor a few feet from the trail.

Matt had run up to the camp for help because between him and Mike they had been carrying just a single snake hook, and they wanted to capture the Bushmaster so everyone could admire it, and this was not a single-snake-hook sort of snake. Within a few minutes Travis and Marisa arrived, and between the five of us we now possessed two snake hooks and two pairs of tongs. And Matt, in a moment of maybe-I'll-find-a-Bushmaster optimism, had thought to pack a large, strong pillowcase, which he was in fact carrying. Matt and Travis both had a lot of experience manipulating venomous snakes, so they manned the tongs. Mike and Marisa used the hooks to hold open the pillowcase. I had neither tongs nor hook, but I had a powerful flashlight, so my job was to keep the snake well illuminated while Matt and Travis maneuvered it into the pillowcase that Mike and Marisa were holding open. After a few tense moments, the snake cooperated and slithered into the pillowcase's open mouth, at which point the hooks were pushed flat to the ground to seal off the opening, and then the bag was twisted shut and knotted.

Success! A bag full of big, heavy, deadly snake!

Mike holding the bag aloft with his expression of triumphant joy (not to be confused with his expression of sleepy bewilderment; those two looks are completely different):

Marisa demonstrating to Mike a more traditional expression of triumphant joy:

Up the hill and back to camp we trudged. After some discussion with camp staff members, the snake spent the rest of the night in its pillowcase, inside a hard plastic tub, with its lid held down by a heavy board that was in turn held down by half a bag of concrete. I have no idea where someone found half a bag of concrete. Marisa wrote out a warning label to keep out the curious. "Shushupe" is a Peruvian term for this snake.

The next day our new Bushmaster friend suffered the indignities of repeated photo sessions, before being returned in the early afternoon to the site of capture, and released there.

photo above by Gina Harper

photo above by Gina Harper

As you can tell, it was a fantastic trip. And despite the dozens and dozens of species we did see, we missed out on seeing dozens and dozens of others. Maybe next year?

John