The first of the two destinations was Madre Selva Biological Station, several hours by speedboat downriver from Iquitos. Madre Selva is owned by Project Amazonas, a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping the people who live in Amazonia and to preserving the forest. Any (small) profits that MT Amazon Expeditions makes from its ecotourist business are used to support Project Amazonas.

Madre Selva encompasses a number of structures hand-built with local materials. Only the building containing the kitchen/dining area/general gathering spot sports electricity, and then only for a few hours each day when the generator is running, around mealtimes. The huts where we slept (called "tambos" locally, a word whose origins seem to be lost to the fog of time) were equipped with mosquito-net-enshrouded beds (generally two people and two beds per tambo) and a little bit of furniture and space on the floor on which to pile our stuff. It was very hot much of the time, very humid all of the time, pouring down rain occasionally, and generally swarming with mosquitos everywhere except under the mosquito nets. In other words, perfect herping conditions!

Local people, often small children, would visit Madre Selva by canoe to bring us critters they had caught in exchange for trade goods we had brought along for this purpose. The trade goods collection mostly comprised t-shirts, candy, and a few hats. Often the local people who dropped by would be wearing t-shirts obtained on earlier herping-group visits. We would hang onto the critters for long enough to satisfy everyone's photo desires (but not longer than a day or so) and then release them.

For reasons perhaps understood only by my subconscious, I am generally not interested in taking photos of animals that I didn't personally see in the wild, so this anaconda is the last such animal that will be included in this account. This silly behavior of mine also means that some of the finest animals we collectively saw at Madre Selva won't be pictured here, because they were found only by other groups of people when I was elsewhere. (Corallus hortulanus! Epicrates cenchria! Cruziohyla craspedopus!) You'll have to beg the other trip participants if you want to see photos of those.

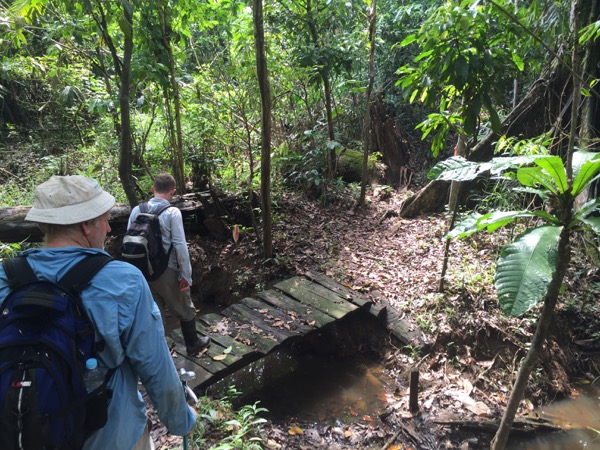

Madre Selva has a well-maintained, though not always well-marked, set of trails through the forest. The standard ones are known as The Short Trail (half an hour or 45 minutes or so at typical speed), The Medium Trail (an hour or two), and The Long Trail (at least two or three hours). I hiked each of those multiple times, by day and night, along with one traversal each of The Deliberate Extra Long Trail (includes most of The Long Trail plus another long not-so-well-maintained chunk intentionally chosen by Julio) and The Accidental Extra Long Trail (includes all of The Long Trail plus a good-sized dead-end extra piece unintentionally chosen by me). My apologies to Cliff and Tom for subjecting them to the latter on the very first night, especially since Cliff had underestimated how much water he should carry. Fortunately Tom had a LifeStraw that came in extremely handy that evening.

Invertebrates of every size, shape, and color pattern occupied every nook and cranny in the forest. I love me some nice bugs, but with all the potential herps to find I couldn't devote too much time to them. Even so, I ended up with a decent collection of Cool Amazon Bug photos, so I thought I'd toss in a few of them here.

On each of my earlier visits to Madre Selva I had seen an amazing leaf-mimic mantid. I didn't see any of those this time, but I did see a few fine specimens of Bark Mantis (Liturgusa sp.) like the one pictured below. I don't know enough insect anatomy to decipher the species definitions in the overview of this genus to tell whether this particular mantis is the one named after the Kratt Brothers (Liturgusa krattorum) or the one named after Al Gore (Liturgusa algorei), both of which are specifically reported from Madre Selva in that overview.

I neglected to deliberately photograph any mosquitos, though many of my photos of other animals include bloodsucking hitchhikers. I did decide to record some evidence of their aftermath, as shown here. Fortunately this was the only type of evidence of their presence that I experienced. (Three trips to the area, and still no botflies, woo hoo!)

Mammal-wise, I don't have much to offer photographically. We saw gray and pink river dolphins, but each sighting was extremely brief as the dolphins exposed only a small portion of their bodies. No photos there. We also saw some monkey activity, which is always entertaining, but the monkeys were way up high and I didn't bother taking any photos since they would have been oh-so-crappy. I saw an armadillo one night as it scuttled across the trail, but didn't get a photo.

The most commonly seen mammals were opossums. In the U.S. we just have the one species that managed to migrate north long ago. But South America is rife with opossum species. I saw a decent number of opossums, but only got decent photos of two of them:

Enough of these furry creatures; let's see some herps! I will start with the frogs and toads, which were by far the most plentiful herps in the rainforest.

Easily seen both day and night were the Crested Forest Toads a.k.a. South American Common Toads, Rhinella "margaritifera". The quotation marks hint that this is widely considered a complex of closely related species that nobody has figured out yet. And it is easy to believe that multiple species are involved with this group of significantly different-looking toads.

Here is a teeny tiny metamorph. The tiny ones tend to be quite colorful if you get close enough to notice.

Some adults have the namesake large crests on their heads. This pointy-nosed fellow has pretty big crests, though it's nowhere near the extreme. One of the characteristics of this species is a triangular-ish head, in the manner of a viper. You can see that here.

This is my favorite leaf-litter camouflage look. No crests on this one, but you can see that the way the jowls kind of bulge out to the side, making that triangular-ish head.

Some individuals have a ridge of pointy tubercles down their backbone.

One species in this area, the Sharp-nosed Forest Toad, has already been split out of the "margaritifera" complex. I am not great at telling them apart, but I think the combination of smooth dorsal skin, upward-pointing snout tip, and lack of triangular-ish head identify this one as R. dapsilis.

But then you get ones like this. The skin is much less smooth than the previous toad, and the snout doesn't have an obviously upward-pointing tip, but it has no significant crests and I see no sign of triangular-ish head. I'm leaning towards "margaritifera", but only the toad's mom knows for sure.

Smooth dorsum, but pretty big crests and the big jowls. I'm guessing "margaritifera" here also.

Very smooth dorsum, no big jowls, but no upward-pointing snout tip either. Darn these toads! I'd like to call this one dapsilis, and who is going to stop me?

Very smooth dorsum, head doesn't look triangular-ish to me, and the slightest hint of an upward-pointing snout tip. I'll call this dapsilis and hope that someone reading this understands these toads better than I do and speaks up. (Jeroen, are you listening?)

Okay, now here's a toad I can identify without hesitation. There are no parotid glands like Cane Toad parotid glands This monster was certainly six inches long, and perhaps seven or eight. And it was probably wider than it was long.

Dendropsophus is a genus of small Central and South American treefrogs that is well represented in Amazonia. Many of them look similar, but a few are quite distinctive. Here's one of the distinctive minority. The parallel longitudinal ridges with some dark highlights and the long skinny shape make this undeniably a Many-lined Treefrog.

The two white spots on the upper lip is the best field mark for this Short-nosed Treefrog, though the blunt snout is obviously a clue also.

Another Short-nosed Treefrog I think, though a less obvious one. That second white spot on the lip is hardly more than a smudge.

This next one is certainly a short-nosed treefrog, but I'm pretty sure it's not a Short-nosed Treefrog (see the importance of capitalizing common names?). It's only got one white spot on the upper lip! That, along with the darker banding, makes me think this is an Orange-shanked Treefrog.

When Matt and I found this amplexing pair, we recognized them right away as Dendropsophus but we weren't sure about the species. It seemed like they would be easy to identify, since we had good photos of both the male and the female, and the white flanks and inky black patches on the female were so distinctive. But the first few references I consulted had no matches. Eventually I found a potential match for the female in a poorly reproduced photo of Dendropsophus allenorum in Duellman's fabulous book "Cusco Amazónico: The Lives of Amphibians and Reptiles in an Amazonian Rainforest". Followup Googling revealed that Dendropsophus allenorum had recently been synonymized with Dendropsophus timbeba.

The charmingly named Hatchet-faced Treefrogs are generally found in or very close to ponds, but on the first night hike at Madre Selva we saw two species, both resting on foliage five or six feet high, and neither near a pond or even particularly close to a stream.

This next little treefrog is reminiscent of the Hatchet-faced Treefrogs, but its face is significantly less hatchet-shaped. It only allowed me one blurry photo before leaping away.

Rocket Treefrogs are one of the most commonly seen large treefrogs in both of the two field stations we visit. This year I only got photos of one from Madre Selva, but it was a particularly fat one.

The Convict Treefrog is so named for the distinctive "prisoner stripes" on its flanks.

Osteocephalus is a genus of medium to large treefrogs with impressive leaping abilities. Here's one in the typical "about to leap really far away from you" pose.

Here's another O. planiceps in a more stable position. This was the first one I had seen with rosy limb stripes.

I believe this larger, blunter-snouted frog is the closely related Giant Bromeliad Treefrog.

On our last night in Madre Selva I was on The Deliberate Extra Long Trail with Emerson and Julio when we heard a very loud, distinctive frog call. Emerson and Julio recognized it as the call of the Amazon Milk Frog, and we all fanned out to try to track it down. Julio found the frog, calling from a water-filled tree hole about five feet off the ground. I attempted to photograph it in the tree hole, but the angle was such that I could barely see it and getting a decent photo was basically impossible. I did manage to capture evidence of the frog's existence, but that's about it.

The most commonly seen and most difficult to identify group of frogs in Peruvian Amazonia is the genus Pristimantis. Every night I saw at least a few of these, and most of them could only be even tentatively identified by comparing details of the photos with the species descriptions from various publications. This process is complicated by the ever-growing number of species in this genus, which already contains more species (470+) than any other genus of vertebrates, and by a series of revisions that split or lumped or re-split or re-lumped species definitions, and by the fact that many species are extremely variable in appearance. Also, some of the distinguishing characteristics involve the color and pattern of the frog's bellies and other hidden areas, and I generally tried to avoid disturbing the frogs too much so I didn't get photos of these areas. So a lot of these identifications are at best educated guesses; I've marked the ones that I am the least confident about with "(?)". If you think I've gotten any of them wrong, please let me know.

One type of Pristimantis whose ID has been eluding me for years is small, generally light-colored, with an at-most barely visible tympanum and a dark-edged "W" mark on the shoulders. I have seen these on all of my visits to Peruvian Amazonia, but hadn't been able to come up with a decent guess as to their identity. I finally have a good idea, though it wouldn't greatly surprise me if I'm completely wrong. The "short" version of the story is: at one point these would have fallen under P. ockendeni, which was later determined to be a species complex. A study of Ecuadorian frogs split out three additional species: P. kichwarum, P. achuar, and P. altamnis, which had three distinct ranges in Ecuador, with the range of P. achuar coming close to northern Peru. Another study later determined that the species P. luscombei had inadvertently been described from a type series that contained specimens of two different species. The type specimen itself retained the name P. luscombei and was redescribed/clarified, and the other species in the type series, which has a very distinctive appearance, was described as the new species P. miktos. Pretty much all photos of P. luscombei older than this recent reclassification (2014) are of the distinctive appearance that identifies them as P. miktos, so it's hard to find photos of the new definition of P. luscombei. However, the P. achuar that had been earlier split from P. ockendeni was then determined to be a junior synonym of the now-clarified P. luscombei, and it's relatively easy to find photos of P. achuar from Ecuador. These photos look very much like my mystery frogs, so I believe these to be P. luscombei. Got that? There will be a short quiz at the end of class.

Another irksome group of rainforest frogs is the group of small Leptodactylus sometimes referred to as "the Leptodactylus wagneri complex". They are distinguished by a set of qualititative characteristics, such as the smoothness of the dorsum, the completeness of the dorsolateral fold, the prominence of the lip stripes, etc. My best guess for these two, which were found near each other, is that they are both Peter's Jungle Frogs, but your mileage may vary.

So many frogs, so hard to identify them. This area of Peru is home to a pair of closely related frogs in the genus Adenomera. They are distinguished primarily (or maybe only? -- this seems to be a point of contention) by call and habitat preference. I did not hear them calling, but both of these were found deep in the forest, which "should" make them Adenomera hylaedactyla rather than Adenomera andreae.

Harlequin Toads (genus Atelopus), are the unwitting poster children of amphibian decline in the New World. Many of the species of beautiful frogs in this genus have been wiped out nearly or entirely in recent decades. Most blame is put on the devastating chytrid fungus, but habitat destruction has clearly also played a significant role. Any sighting of these frogs in the wild is a wonderful but bittersweet event. One particular stream crossing on the trails of Madre Selva has been a reliable location for the local Atelopus species, and one morning when I hiked the Long Trail by myself I was lucky enough to spot a single individual of this mostly diurnal species.

Later, when I hiked The Deliberate Extra Long Trail with Emerson and Julio, I saw another one sleeping in the vegetation at night. This was a good distance away from the stream crossing location, which is a hopeful sign.

The most commonly seen poison frogs in the area are two very similar looking species that were once placed in the same genus but these days are placed in different families (at least according to the taxonomy used by the American Museum of Natural History).

The largest poison frog in the area is the striking Three-striped Poison Frog. On my two previous visits I had missed out on seeing any wild ones, but this time I was lucky enough to see three. I was having camera troubles when I saw the third one, but here are photos of the first two.

And one of the smallest poison frogs in the area is the Uakari Poison Frog, even more beautiful than the Three-striped. These are closely related to the poison frog we saw on the grounds of the Iquitos zoo, but can be distinguished by some differences in the striping and coloration. I managed to come across four or five of these little gems at Madre Selva.

At least three species of salamander can be found in the area, all in the neotropical genus Bolitoglossa. They all look similar and have similar lifestyles. They are found climbing on wet rainforest leaves at night, often in a near-vertical position, using their cute little padlike feet. From the length of the tail, I believe this one to be the Peruvian Climbing Salamander.

This one has lost the most important clue as to its species. However, the parts that remain are so similar to the previous salamander that I am reasonably confident it is the same type.

Skink-wise, this area offers only a single fairly nondescript species, the South American Spotted Skink. It is easy to find along trails and in treefalls and in other open areas of the forest when the sun is shining.

Forest Whiptails shared the sunny patches with the skinks. I often saw the two species just a foot or two away from each other. This is a very young lizard, at an age when their colors are brightest.

Microteiids a.k.a. Gymnophthalmids are a family of small lizards typically found scuttling through leaf litter or alongside forest streams. A number of species are in the area, but I only saw one at Madre Selva this time.

Also scuttling through leaf litter are the awesomely camouflaged Western Leaf Lizards, which have a body plan very similar to Sceloporus but with colors and strong-edged patterns that provide them near invisibility when resting in dead leaves on the forest floor.

However, camouflage only works with the right background. One afternoon we came across two Western Leaf Lizards in quick succession that had apparently not figured this part out. These are both in situ, believe it or not.

Various anoles inhabit the forest. Mostly we would see them sleeping in the foliage at night, but occasionally we'd see one during the day. This is not at all similar to the anole situation in, say, Florida. The night-sleepers would usually notice our presence quickly and open their eyes.

Although there are only seven or eight anole species in the area, it is still not always easy to identify them. For example, female A. trachyderma look very similar to female A. fuscoauratus, and A. chrysolepis can easily be confused for A. bombiceps without a careful look at the dewlaps. So I probably have some of these wrong.

Amazon Forest Dragons are another reasonably common diurnal species that I've encountered mostly as they rested at night. On my three visits together I have seen at least a dozen individuals, but only one by day.

Only a few species of geckos live in the area, which has always surprised me. By far the most commonly seen are two species of diurnal Gonatodes, none of which I managed to photograph in Madre Selva this year. The one big gecko is the Southern Turnip-tailed Gecko, which is most often found on the field station buildings. As usual, at least one individual patrolled the bathroom building interior walls as entertainment for us. Another one guarded the building where the "photo studio" (a couple of tables with big leaves scattered on them) was set up. We detained this one for a day so people could get good photos. I had failed to get an in situ photo when the gecko was on the building, so I took a couple of shots when it was in the building instead.

My favorite lizard of the trip was perhaps the tiniest, a species that I hadn't seen before and has been encountered only rarely on these trips. I spotted this inch-and-a-half long Amazon Pygmy Gecko resting on a dead leaf on the forest floor on the first night at Madre Selva, and it was kind enough to remain on the leaf long enough for me to get two photos before ambling into the leaf litter. We tried to rediscover it since we knew other people would want photos, but it had made its escape.

Finding snakes in the rainforest is rarely easy, but we got off to a particularly slow start at Madre Selva. On the first night, the group I was with took The Accidental Extra Long Trail but still didn't see any snakes, and if I recall correctly neither did anyone else. On the second night, I did The Long Trail with a set of people including the local guide Edvin, who is the best snake spotter in Peru as far as I can tell. Still, we came away with only one snake, an Aquatic Coralsnake that was perched on the exposed part of a submerged log and drinking from the stream.

I don't remember what other hiking groups saw on the second night snakewise, but it wasn't much if anything.

On the third night, about half of the people went out in a boat to look for Amazon Tree Boas and caiman and to check out the goofy Fujimori Sidewalk (goofy in that there is extremely little practical purpose for a paved path in this area, and there is no actual road for it to be a sidewalk for; it had been a bit of political pork by former Peruvian president Fujimori designed to attract votes). The other half took The Long Trail. We boat-going people had yet another weak snake night; we did manage to see a couple of the local water snakes (Helicops angulatus) along the Fujimori Sidewalk, but we didn't find any tree boas. And I personally didn't even see the water snakes while they were still wild, so I don't have any photos of them. The Long Trail people had much better luck: they ended up seeing seven snakes, including two gorgeous Peruvian Rainbow Boas.

On the fourth night, I hiked The Long Trail with Emerson, Edvin, Matt, and Tom. This time we were sure we'd have some good snake action, since the previous night had been so fruitful. But alas, the only serpent we encountered was a single Blunt-headed Tree Snake. I definitely love Blunt-headed Tree Snakes, but they have been the most commonly seen snake on each of my visits to Peru so it was not the very most exciting find.

The following morning I was out on The Long Trail again, this time with Matt, Cliff, and Kevin. Our primary objective was to find Atelopus spumarius at their usual spot. We had reached that location and spread out to search for the frogs when I heard Kevin shout out "Snake!" followed by much crashing through vegetation as Kevin chased the snake down an embankment and into a stream. The stream was three feet deep at most, so Kevin was undeterred and continued to splash noisily in hot pursuit of the hapless serpent that was swimming rapidly downstream. Matt called out "What kind of snake??" and Kevin yelled back "I think it's a water snake!". I was on top of the embankment on the other side of the stream and could now see the snake and Kevin fairly clearly. I shouted out "I think it's a Fer-de-Lance!". Kevin shouted again "I think it's a water snake!". I replied with "I'm pretty sure that's a Fer-de-Lance!". Now Cliff could see it also and he too joined in with "I think it's a Fer-de-Lance!". Kevin had gotten close enough to the speedily swimming serpent that he could have grabbed it by the tail, and he was considering doing just that, but something in the voices of me and Cliff (perhaps it was the actual words) slowed his hand, and he chose not to make contact. This was wise, as it was most definitely a Fer-de-Lance. The snake swam to the far side of the stream and hunkered under an overhang in the bank. We all hurried over. Kevin and Matt wrangled it out into the open with tongs, and we got a few photos with the snake in the water.

Matt then wrangled it out of the water and up to a fairly open spot on the trail, where we encouraged it to coil for more photos before we let it slither off back into the forest.

That evening was our last at Madre Selva. I was determined to find some more snakes, so as mentioned earlier I joined Emerson and Julio on The Deliberate Extra Long Trail. We got off to an auspicious start; no more than fifty yards from the start of the trail a bit of color caught Julio's eye and in an instant he was extracting a bright red-and-black snake from a root tangle. I wanted to get a photo of the snake in the forest where it was found (though no longer in situ), but it would not cooperate quickly and I didn't want to hold up Emerson and Julio for long since we had an Extra Long Trail ahead of us. So I gave up quickly and we bagged the snake for photos the next morning. This is the best shot I got in the forest:

At the time we found it, I thought the snake was another Amazon Scarlet Snake like the one we had seen on the Nauta Road in Iquitos. But counting the scale rows revealed that it was instead a lookalike species, the Amazon Egg-eating Snake a.k.a. Black-collared Snake. Here's a photo I took the following morning before releasing the snake back where it was found.

Five minutes later, Emerson spotted a small black-and-white snake near the ground. I recognized this one from an earlier trip as a Banded Calico Snake. Emerson had picked it up before I had the chance to tell him I wanted to get a picture in the forest, so he let it coil around a stick so I could get this award-winning photo (not).

Not too long later, I noticed another Blunt-headed Tree Snake. This night was shaping up well, snake-wise!

We then hit a snake dry spell for a couple of hours, and had gotten deep into the Extra part of The Deliberate Extra Long Trail. We had seen a fine collection of frogs, bugs, and opossums along the way, so I was quite satisfied with the night's hiking. But I became even more satisfied when a coiled Green-striped Vine Snake caught my eye. We had found a DOR Brown Vine Snake back on the first part of our trip in Panama, and Ryan in particular had been dying to see a live vine snake ever since. So I knew this one would bring some smiles onto faces back at camp, and indeed it did. The next morning there was much vine-snake-fondling by Ryan and others.

No more than ten minutes later, another sleeping colubrid stopped me in my tracks. I recognized this one right away from earlier trips as a Tawny Forest Racer.

So I ended up seeing five snakes on my last night at Madre Selva, which is a fine haul for the Peruvian rainforest. (I must admit that I was especially proud to have found three snakes that both Julio and Emerson had missed, because they don't miss much.) The snake diversity was starting to heat up. The next day we headed to our second destination, Santa Cruz Forest Reserve, which has been a good spot over the years for finding Bushmasters. Would we be so lucky this time?