I should warn the ophidiophiles right now that the word "herping" in this story does not mean "finding snakes". I did have some hope of finding some snakes, and some frogs, crocodilians, amphisbaenians, tuataras, etc., but I was sure that I would find some lizards. And in the end lizards were all I saw. So if you are one of those people who only like the particular group of legless lizards that for some reason is placed in a different suborder than other lizards, you should just turn away now.

Puerto Rico

We started with a few days in Puerto Rico before boarding the cruise ship. We stayed in Old San Juan, considered the second-oldest city in the New World, after Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola. (Of course, this definition of "city" excludes the Incas and Mayans, etc.) Old San Juan is guarded by two large forts that are now part of the U.S. National Parks system. The smaller one, Castillo de San Cristóbal, guards the land entrance to the city. My first Puerto Rican herp was this colorful Common Iguana (Iguana iguana) that was basking on the top level of the fort:

Habitat shot:

The other large fort, Castillo San Felipe del Morro, guards the sea entrance to the city. It too has its very own iguana population keeping the tourists honest:

Habitat shot:

One day we hired a cab driver to show us some sights, including El Yunque, which claims fame as the only tropical rainforest in the U.S. National Forest system. (Yes indeed, Puerto Rico is part of the U.S., in case anyone wasn't paying attention in high school.) On the way to El Yunque we stopped briefly at a small cave named Cueva María de la Cruz. I headed straight for the rocks and vegetation when we got out of the car, but the rest of my party headed straight for the bathrooms. On their way back cave-ward, my mother-in-law let out a little yelp when she spotted a bright green baby iguana in the (mostly dried-out) grass:

Habitat shot (note cave in background):

The cave was perhaps a tad disappointing in its actual cave-ness, as (A) it was quite shallow, and (B) it contained no obvious bats. But, the rocky geologic formations and vegetation were a happy home for many lizards. Most noticeable were a dozen or so Puerto Rican Giant Ameivas (Ameiva exsul exsul) that scurried to and fro, just occasionally pausing long enough to have their images recorded for posterity:

Watching the rocks and trees revealed a bunch of anoles. At the time I didn't know whether multiple species were involved, but I now believe (with some confirmation from the knowledgeable folks at Anole Annals) that they were all Puerto Rican Crested Anoles (Anolis cristatellus cristatellus). I had seen these trunk-ground anoles before in the Dominican Republic and in South Florida, but it was nice to see them in their native habitat.

Anolis cristatellus cristatellus was also plentiful in El Yunque itself, especially in more open habitats and around forest edges. Here are a couple more of the many I saw in a few brief stops at El Yunque:

Other than the Green Iguanas and Puerto Rican Crested Anoles, all of the lizards I saw on this trip were species (or, in one case, subspecies) that I had never seen. My first lifer species was this pretty Puerto Rican Emerald Anole (Anolis evermanni), a trunk-crown anole like the USA's very own Anolis carolinensis. Trunk-crown anoles tend to be fairly high on tree trunks or branches, and they tend to be green for good camouflage against a leafy background. This one, however, was not in a tree at all, but on a post on the walkway bridge to the El Portal visitor center at El Yunque.

Habitat shot:

We only had a couple of hours in El Yunque, and part of that time was spent at the visitor center, and another part at a roadside snackeria (I think I made that word up). We went on one very short hike to a waterfall, but I didn't spot any herps there, possibly due to the slightly drizzly weather. We were intending to go on another short trail, but that one turned out to be closed for some reason. However, by the bathroom at the parking lot for that trail, I spotted another new anole while others were on a bathroom break. This is an Olive Bush Anole (Anolis krugi).

The next day we visited the Arecibo Observatory, home of the world's largest single-dish radio telescope. (I believe I am contractually obligated to mention that this dish was featured in the films Contact and Goldeneye, at least.) We were there for perhaps half an hour. In that time I saw a video about the history of the observatory, admired the giant dish itself, and photographed three species of anoles.

I thought this one might be something new to me, but was later convinced that it is yet another variation in appearance of Anolis cristatellus:

Habitat shot:

My favorite anole on Puerto Rico was this crazy-long-tailed Puerto Rican Bush Anole (Anolis pulchellus). I first saw it on a post on the visitor center patio; later it had moved down into some potted plants. These are purported to be the most common anole on Puerto Rico, but I only saw two of them, compared to perhaps a hundred Anolis cristatellus cristatellus, so I guess I wasn't looking in the right places.

Anole number three at Arecibo was this Puerto Rican Spotted Anole (Anolis stratulus), one of the trunk-crown anoles that isn't green:

St. Thomas

From Puerto Rico we boarded our cruise ship and visited various islands for one day each. Our first stop was St. Thomas, one of the U.S. Virgin Islands. St. Thomas was connected to Puerto Rico during the last Ice Age, so its fauna is essentially a subset of the fauna of the much larger Puerto Rico.

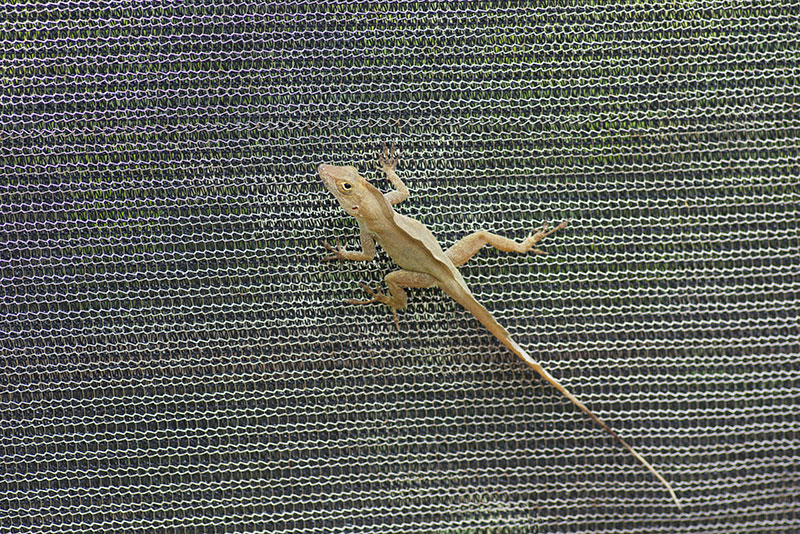

Monica and I went scuba diving on our morning in St. Thomas. It was great, but we didn't see any reptiles (not sure where the sea turtles were hiding at that point). That afternoon we visited a small Butterfly Farm and Botanical Garden extremely close to the cruise dock. It was a small oasis of vegetation in a mostly paved-over area, so it looked inviting. The netting for the butterfly enclosure was not in the finest of repair, which was fine with me because it meant there were lots of gaps for the local anoles to get in. These are all crested anoles of various ages and genders, though the ones from St. Thomas are considered a different subspecies, the Eastern Crested Anole (Anolis cristatellus wileyae):

Just to prove we were actually at the Butterfly Farm, here is an Emerald Swallowtail (Papilio palinurus).

A couple of other familiar saurian friends from Puerto Rico put in appearances for me on the grounds of the Butterfly Farm and Botanical Garden. This massive iguana let me take one photo before it thundered off into the bushes:

And some more Ameiva exsul exsul were poking around in the bushes and basking on the footpaths:

Still later that day, Monica and I took a walk along a path that mostly paralleled the shore. In front of a cruise-dock shop I finally found a cooperative ameiva, though it was just a youngster with a regenerating tail:

A few iguanas hung out on a rocky seawall. Perhaps they were dreaming of the Galápagos?

Habitat shot (featuring Monica and our cruise ship):

Barbados

After St. Thomas we spent a day at sea to cruise way down into the southern Lesser Antilles, where each island has either one or two native anole species, and perhaps an ameiva species. On our next stop, Barbados, we took a nearly-whole-day-long van tour to various "highlights". I had been warned by Matt Cage that there is very little natural habitat left on this overdeveloped island, and he wasn't wrong. Even most of the areas that weren't covered with buildings looked like they had been scraped clean of native plants:

We stopped high up on a hill for a five-minute scenic view opportunity, which I inattentively turned into a ten-minute lizard hunt in some nearby bushes. I felt guilty when I was the last one back to the van, since we were trying to hurry to get to the rum place before the next tourist busload. But hey, I found a lizard! This is a juvenile Barbados Anole, Anolis extremus, the only native anole on this island:

A few minutes later our road was mostly blocked by some big truck, and we still hadn't made it to the rum place yet! What to do, what to do. After a moment of thought, it was determined that if we all got out of the van then the driver could probably get it past the truck, and if he ended up turning it over in the roadside ditch then at least there wouldn't be a bunch of angry and potentially litigious tourists in it. So we got out for a few minutes, and the van got by with no problems. Those few minutes were enough time for me to find Barbados Anole number two, this one a big, beautiful, ugly adult:

After the rum stop and a few other less interesting stops, we returned to the cruise dock. Monica and I decided to walk through a narrow strip of parkland into town to stretch our legs. This turned out to be a good move, because many of the trees in the parkland were occupied by more Anolis extremus:

St. Lucia

The next day we visited nearby St. Lucia, another one-native-anole island. Once again, we were on a nearly-whole-day-long van tour, so I could only look for herps at the preordained short stops.

Our first stop that featured any vegetation was a scenic overlook. I let everyone else look over at the scenery while I searched the vegetation for anything scaly. I was rewarded with my first Saint Lucia Anole (Anolis luciae):

Scenic view that I mostly ignored:

The only other stop of herpetological interest was a waterfall popular with tourists, or at least popular with tour operators. Before we arrived we had entertained the notion of swimming in the waterfall's pool, but when we saw how many other people were already doing so, we decided to just admire it from a distance. And, of course, look for anoles:

Habitat shots:

St. Kitts

After St. Lucia came St. Kitts, a two-native-anole island, which is non-obviously named after Christopher Columbus. We had opted for a "Rail and Sail" excursion, which started with a ride on a small-gauge tourist train that was once used by the sugar industry, and ended with a catamaran ride back to the cruise dock. The train ride was relaxing, with nice scenery, though it might perhaps have been more relaxing if I hadn't been carefully studying every bit of passing vegetation for herps. I ended up spotting about a dozen large green anoles, and a few smaller brown ones. The large green anoles were certainly Statia Bank Tree Anoles (Anolis bimaculatus). The smaller brown ones might have been Statia Bank Bush Anoles (Anolis schwartzi), but they might also have been young non-brightly-colored Anolis bimaculatus. Since I only saw each one for a second or two, I'll never know.

Between the Rail and the Sail, we had fifteen minutes or so of waiting for transportation from the end of the rail line to the catamaran dock. There was grass, and there were some bushes in the grass, so naturally I looked for anoles. And I found one large and beautiful one, but it did the "squirreling" trick to try to stay concealed, so I don't have a photo that shows how pretty it was.

Habitat shot:

The catamaran ride featured unlimited drinks, nice weather, and ocean, but no herps. Afterwards we walked around a little in the cruise dock area, where I spotted a couple more Anolis bimaculatus, though none as large and colorful as that first wary one.

In addition to the anoles, the cruise dock area also featured Orange-faced Ameivas (Ameiva erythrocephala) decorating the pavement:

Habitat shot:

Sint Maarten

Our final stop was Sint Maarten. We didn't take any guided excursion here, so I had a little more time to wander around near the cruise dock and spot the local lizards. Sint Maarten is a two-native-anole island, but I only saw one of the two species, the Anguilla Bank Tree Anole (Anolis gingivinus). Happily, I saw a lot of them.

Sint Maarten's ameiva is the relatively unremarkable Anguilla Bank Ameiva (Ameiva plei). As on the other islands, the ameivas on Sint Maarten seemed particularly happy around human habitation.

This one seems to be doing its best varanid imitation:

In my wanderings I came across a freshwater canal. Part of it had dirt banks, and part of it was lined with concrete. Both parts featured plenty of Iguana iguana. It's smaller cousin, the Caribbean's indigenous Iguana delicatissima, used to live on Sint Maarten but has been extirpated from there as well as from many other islands.

Seeing a bunch of different anole species made me want to learn more about them, so when I got back from this trip the next book I read was Jonathan Losos's wonderful "Lizards in an Evolutionary Tree: Ecology and Adaptive Radiation of Anoles". Now I have the anole bug, and I hope I have the opportunity to visit many other parts of the Caribbean someday to see lots of different anoles. Probably not on a big cruise ship, though.

John